While Oregon leads the nation in number of units in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSRS), Oregon trails in (1) total number of protected wild and scenic river miles, (2) total acreage within the NWSRS, and (3) percentage of the state’s total stream mileage protected in the NWSRS. Through the initial leadership of Senator Mark Hatfield (R-OR), the historical leadership of Representative Peter DeFazio (D-4th-OR), and the current leadership of Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), Oregon can be proud of having had three congressional champions for the protection of free-flowing streams for the benefit of this and future generations.

Any well-run business has its key performance indicators (KPIs) to judge the health of the firm beyond its current balance sheet and profit-and-loss statement. Let’s delve into the pertinent KPIs for Oregon’s place in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

KPI #1: Number of units in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System

Winner: Oregon

Of the 242 total units of the NWSRS nationwide (Table 1), Oregon has 68 units, approaching three times more than the next state (California). Indiana, Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have none. It should be noted that several of the units in California contain not only mainstems but also numerous forks and tributary streams. At the other extreme, in Oregon the Spring Creek WSR measures 1.1 miles long and is in fact a tributary of the much longer Jenny Creek WSR. As both will be effectively managed as one WSR, they should have been designated as one WSR.

KPI #2: Total wild and scenic river miles

Winner: Alaska

First runner-up: Oregon

Alaska has 3,210 miles of free-flowing streams in the NWSRS, while Oregon has 2,136.1 (Table 1). The average length of a WSR in Alaska is 128.4 miles, while in Oregon it is a mere 31.4 miles.

However, for the reason stated in KPI #3, KPI #2—as far as comparing Alaska to Oregon (or any other state)—results in false equivalency.

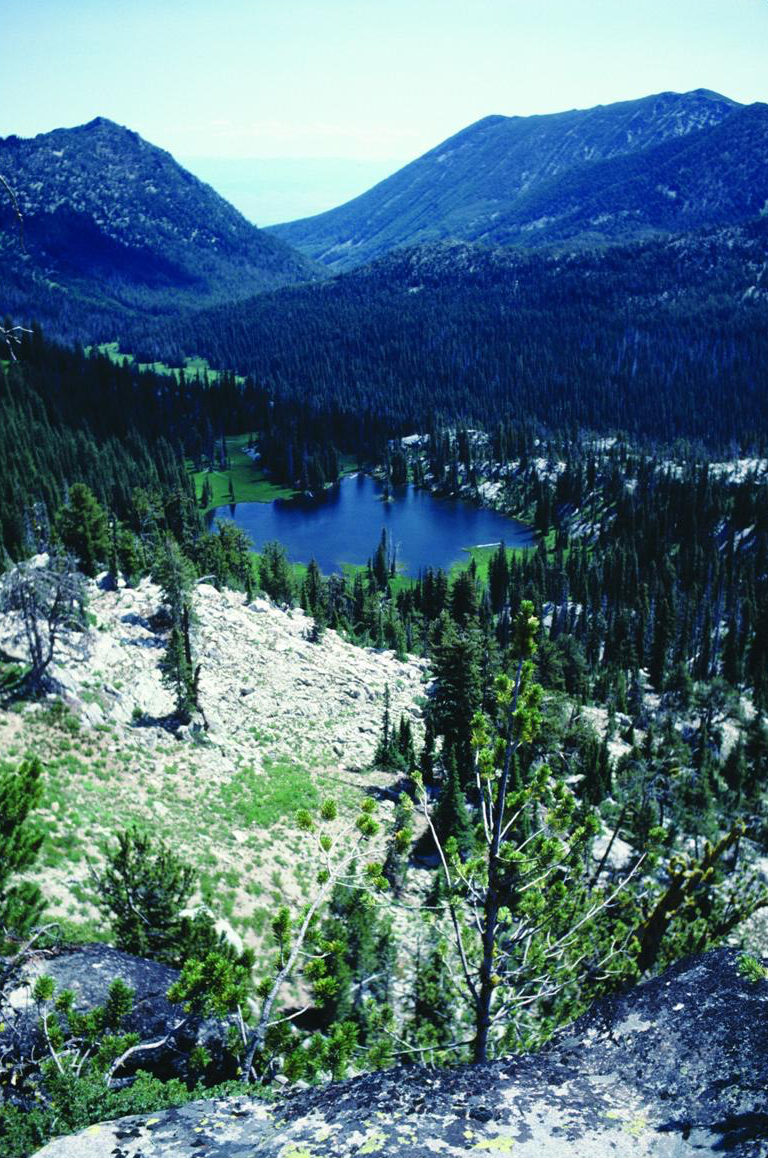

Figure 2. Dutch Flat Lake in the Elkhorn Mountains, the source of Dutch Flat Creek. Both should be included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Source: George Wuerthner. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness by the author.

KPI #3: Total acreage protected in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System

Winner: Alaska

First runner-up: Oregon

Stream miles in the NWSRS is a measure that indicates only the length, not the width of the protected area along that stream. The default setting of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 (WSRA) as amended is that when the administering agency draws the “detailed boundaries” of a WSR, it can include no more than an average of 320 acres per linear mile of stream. If a stream in a WSR were (im)perfectly straight, this would result in a buffer one-quarter mile wide on each side as measured from the center of the stream. However, for all of the WSRs in Alaska, Congress directed that the protected area be no more than an average of 640 acres per stream mile, resulting in a theoretical average one-mile-wide protective corridor.

Fortunately, theory is not practice and streams are not perfectly straight (save for those later engineered), so natural meanders result in extra acres being available in the protected area.

Of Oregon’s sixty-eight NWSRS units, only three (Elkhorn Creek, Fifteenmile Creek, and Elk Creek) are congressionally blessed with “fat buffers.” For a given mile of an Oregon WSR, the average protective width is about half that of a given mile of an Alaska WSR. Given all the meanders of streams and whims of bureaucrats, the amount of Oregon land in the NWSRS is ~731,000 acres. If WSRs in Alaska had the same average meander as Oregon WSRs, the amount of land in Alaska in the NWSRS would be ~1,098,502 acres (only an estimate as no central GIS layer has been created to measure area [acreage] within the NWSRS).

Another way to look at it: A mile of an Alaska WSR goes twice as far (actually, goes twice as wide) as a mile of an Oregon WSR.

Figure 3. Old-growth forest along Bitter Lick Creek, a tributary to Elk Creek and just above the wild and scenic river portion established on Elk Creek in 2019. Bitter Lick Creek, along with other tributaries to Elk Creek, should be added to the Elk Creek Wild and Scenic River. Source: Ken Crocker. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness by the author.

KPI #4: Percentage of a state’s streams that are national wild and scenic rivers

Winner: New Jersey (4.367%)

First runner-up: Delaware (4.102%)

Second runner-up: Rhode Island (3.951%)

Third runner-up: Connecticut (2.696%)

Fourth runner-up: Oregon (1.925%)

New Jersey rocks! For the GIS stream layer used in this analysis, Oregon has 1.16 miles of stream per square mile of land (not including large bodies of water, salt or fresh). Compare that to New Jersey (0.88), Delaware (1.12), Rhode Island (1.35), and Connecticut (1.20). It must be a Northeast US thing that its citizens and elected officials more appreciate the precious little wild and scenic that remains since the rest of it has been so trashed.

Figure 4. A dunal wetland in the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area. Wetlands, lakes, and streams in the recreation area would be unique additions to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Source: Dominic DeFazio. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness by the author.

KPI #5: Wild and scenic river rankings of the Oregon congressional delegation

Senate winner: Mark Hatfield

Senate first runner-up (so far): Ron Wyden

House winner: Peter DeFazio

House first runner-up: Ron Wyden

KPI #5 is somewhat quantitative but based mostly on the qualitative judgment of the author. The quantitative is the miles of WSRs in Oregon the elected official voted for, while the qualitative is the leadership shown (a.k.a. political capital expended) to actually get those Oregon WSRs established by law.

Senate Hero, Emeritus

Senator Hatfield is the Senate winner, partly because he served in the Senate so long but mostly because he was generally a wild and scenic river champion. One of the first eight WSRs established under WSRA was the (lower) Rogue WSR in Oregon. It happened because Hatfield was in the Senate in 1968 and wanted it.

The original vision and framework of WSRA was that for additions to the NWSRS, first an act of Congress would be passed to require a federal agency to study the stream segment for WSR status and make a recommendation to Congress. Then it would take another act of Congress to actually establish the WSR. Until 1988, this was the case for most streams, including in Oregon the Illinois, the mainstem Owyhee (also then called the South Fork), the lower middle Snake (in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho), and the North Umpqua.

In 1988, Hatfield in the Senate (and DeFazio in the House, as told below) enacted into law the Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. In that law, Congress established forty-one NWSRS units in Oregon totaling 1,441 miles, with none having had a previous congressionally authorized agency study. This was unprecedented not only in magnitude (previous WSR study and designation bills named one stream in each bill) but also in the fact that it blew away the need for an act of Congress to merely evaluate a potential WSR. Why did Hatfield do this? I think it was both to secure his place in history and to mitigate concurrent horrendous environmental sins he was committing as a matter of political necessity.

In the 1980s, the largest and most acute dam threats in Oregon were the proposed Elk Creek Dam on a tributary of the Rogue River and the proposed Salt Caves Dam on the Upper Klamath River near the California border. Hatfield championed the Elk Creek Dam beginning when he was governor of Oregon in 1962, when Congress authorized the Elk Creek Dam. Opposition to the Elk Creek Dam was broad and deep, but while Hatfield’s support was narrow, it certainly was not shallow. Despite near-universal condemnation by the editorial boards of most of the state’s major newspapers (which counted politically back then), Hatfield pressed on to damn Elk Creek. (See Appendix A below for the short version of the epic fight for, loss of, death to, win for, and rebirth of Elk Creek.)

The City of Klamath Falls very much wanted to dam the last free-flowing stretch of the Klamath River in Oregon, and Hatfield didn’t want to stand in the way but was under pressure to do something. In his 1988 bill, Hatfield gave the Upper Klamath a half-assed (a congressional term of art) wild and scenic river “study” (not as good as a real WSR study requirement and certainly not inclusion in the NWSRS).

Besides loving Elk Creek Dam and not hating Salt Caves Dam, Hatfield, as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, was funneling record-sized appropriations to the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to liquidate Oregon’s ancient forests. In 1989, just before the northern spotted owl hit the judicial fan, three square miles of Oregon’s old-growth forest on federal lands were being clear-cut each week. Hatfield saw his record-sized Oregon Omnibus Wild and Scenic Rivers Act as political mitigation for his double-dam(n) sins and also for his cardinal sin of old-growth liquidation. To a large degree, it worked.

Figure 5. Grande Ronde Lake in the Elkhorn Mountains, a source of the Grande Ronde River. The upper Grande Ronde River should be included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, as is the lower Grande Ronde River. Source: George Wuerthner. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness by the author.

House Hero

In 1987, Peter DeFazio started his first term in the House of Representatives (he’s now in his seventeenth term). DeFazio had campaigned in opposition to the Salt Caves Dam and in December 1987 introduced legislation in the House to add the Upper Klamath to the NWSRS. The first-termer was forcing Oregon’s very senior senator to do something. Since he didn’t want to save the Klamath, Hatfield’s response was to introduce Oregon WSR legislation that appeared to save everything but the Upper Klamath. DeFazio pushed Hatfield’s bill through the House and it became law—without the Upper Klamath.

Fortunately, that same year the people of Oregon voted to include the Upper Klamath and several other Oregon streams in the Oregon Scenic Waterways System. In 1992, Governor Barbara Roberts (a Democrat), with the strong support of DeFazio, convinced Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt (a Democrat) to include the Upper Klamath Oregon Scenic Waterway in the NWSRS via an alternative path outlined in WSRA that didn’t require an act of Congress.

DeFazio, by calling a tough political question on the Upper Klamath, forced Hatfield (along with the senator wanting to mitigate other environmental sins) to do a single mega-multi-WSR “instant” (no study) designation bill. Today, congressionally mandated studies are so rare that the political term of art “instant designation” has fallen out of use.

In his later terms, along with Wyden in the Senate, DeFazio shepherded through the House the designation of some WSRs on Steens Mountain in 2000 and on and around Mount Hood in 2009, the addition of the North and South Forks of the Elk River to the NWSRS in 2009, and the designation of the nation’s first subterranean wild and scenic river (the River Styx in the Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve) in 2014.

Senate Hero

Senate hero Hatfield eventually retired and House hero DeFazio has not again reached his initial wild and scenic river peak. For Steens in 2000 and Mount Hood in 2009, most of the heavy WSR lifting was in the Senate, as was the case for the ten new WSRs in Oregon designated in 2019. The result is that Wyden is unambiguously the current wild and scenic river champion of the Oregon congressional delegation. Wyden took the leadership mantle after Hatfield retired. While Wyden voted for (and co-sponsored) Oregon WSRs while serving in the House (1981–1995), he wasn’t a champion in that legislative body.

In terms of Oregon WSRs, Wyden still has a long way to go to surpass Hatfield’s and DeFazio’s Oregon WSR leadership mileages (1,418 and 1,469 more miles respectively, but who’s counting?) (Table 2). Fortunately, Wyden is positioned not only to surpass Hatfield’s and DeFazio’s WSR records of accomplishment but also to help Oregon surpass Alaska in both WSR miles and—the most important key performance indicator—NWSRS protected acreage.

Of course, so is DeFazio.

Figure 6. A segment of the Nestucca Oregon Scenic Waterway, established in 1988, downstream from the Nestucca Wild and Scenic River, established in 2019. It flows through the proposed Mount Hebo Wilderness. Source: Erik Fernandez. First appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness by the author.

Appendix A: The Dam Saga of Elk Creek

Even though the US Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) said that the Elk Creek Dam was a fish killer and a budget buster since it was first authorized by Congress in 1962, Senator Hatfield persevered in supporting it over the decades. Conservationists and anglers were able to block construction because a combination of factors lined up, including but not limited to opposition by the Oregon governor, opposition by the local member of Congress, and opposition by the Army Corps of Engineers. With the political coattails effect of Ronald Reagan becoming president in the 1980 elections, Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time since 1954. Hatfield became chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee and eventually put the commanding general of the Army Corps of Engineers in a political headlock, threatening the agency’s entire budget if it didn’t start construction of the Elk Creek Dam.

In addition, when Oregon’s congressional districts were redrawn after the 1980 census, the Elk Creek Dam site moved from the 4th District, then represented by Congressman Jim Weaver (D-OR), who opposed the boondoggle, to the 2nd District, then represented by Congressman Bob Smith (R-OR), who supported it. The final nail in the coffin was that Oregon’s governor at the moment was Republican Vic Atiyeh, who supported the dam. The evil stars had all aligned and construction commenced.

A coalition led by what is now known as Oregon Wild sued over the dam but lost in district court. The Ninth US Circuit Court of Appeals failed to grant a stay pending appeal, so construction commenced. Nonetheless, when the dam was half built, the Ninth Circuit ruled in our favor and construction was halted pending further environmental reviews.

The case went to the US Supreme Court, which ruled against us on three of the four issues we had won on in the Ninth Circuit. For reasons I will likely never know, the government had appealed only three, not the fourth, issue. So even though we lost in the Supreme Court, dam completion was still stayed pending further environmental review.

The ACE was slow-walking the environmental reviews and had instituted a trap-and-haul facility to transport migrating salmon around the half-built dam. As soon as Hatfield announced he would not seek re-election in 1996, the Army announced that since the trap-and-haul facility wasn’t particularly effective to transport coho salmon that were now protected under the Endangered Species Act, the Army would “notch” the dam, allowing Elk Creek to again flow free and the salmon to migrate without needing an internal combustion engine. After the Army’s contractors completed the “notch” (using heavy explosives), kayakers immediately reclaimed the free-flowing stream.

Hatfield, who could easily have attached a rider to a vital piece of legislation that would have mooted any legal challenges conservationists might bring, never did. Did he have second thoughts about the Elk Creek Dam after all those decades of support? Did he think he didn’t have the political capital to do riders to both liquidate old-growth forests and finish the Elk Creek Dam? Did he think he’d be blocked if he tried and thereby lose face? (I thought he could do it.) We’ll never know. I regret not asking him this question after he left office and before he died.

In 2019, due to the leadership of Senator Wyden, Congress established the stream along the damsite and the prospective reservoir pool area as the Elk Creek Wild and Scenic River (with fat buffers) and also deauthorized, once and for all, the Elk Creek Dam.