Summer is over in the Rogue Valley of southern Oregon. Temperatures have dropped and the smoke is far less. More mixing of the atmosphere is lessening inversions that trap smoke, and the cooler weather is cooling the forest fires still burning. The rains will soon come and extinguish them.

As public forestlands in the West cover more area than private timberlands, most of the smoke that plagued the Rogue Valley this summer came from public lands on fire. This might lead one to think that more logging on federal public lands would help, but one would be wrong. Realizing that forest fires are ecologically beneficial and taking steps to prevent preventable particulate pollution while adapting to the new reality of smoke season will go farther toward preserving functioning forest ecosystems.

Figure 1. The ecologically beneficial Taylor Creek and Klondike Fire of 2018 burned on the Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest, Oregon. Source: US Forest Service.

Our New Season

Climate change is bringing us a new season each year in addition to the conventional four. Superimposed on winter, spring, summer, and autumn in the Rogue Valley is the season called fire. It’s mostly in the summer but not always continuously, and it’s beginning earlier in the spring and ending later in the fall. In southern California, the fire season is becoming all year. (On the Pacific coast, they also talk of the hypoxia season, the time when the warming ocean produces toxic algal blooms. The blooms are happening more often and more intensely as the ocean warms.)

This fire season (or maybe I should say smoke season), the smoke came in July and was mostly bad through September. Air quality (Table 1) was rarely either good or hazardous but was often unhealthy for sensitive groups or unhealthy for all, and was sometimes very unhealthy for all. Whatever the air quality index (AQI) was, the air quality was chronically, annoyingly, and depressingly not good. A moderate AQI was considered a great day.

Table 1. Whether to breathe deeply or not. Source: airnow.gov.

Masked humans became common around Ashland. Many of the masks, I would note, were not doing the job, as only NIOSH-certified N95 or P100 respirators adequately filter out the PM 2.5 particles (particulate matter <2.5 microns)—particles that are inhaled but never exhaled. The masks work only if worn properly. (They don’t seal well on people with beards, and no, I didn’t shave my beard of fifty-one years.)

Chronic smoke is not only irritating to one’s sunny disposition but also a major cause of asthma and heart disease.

Why Is It Happening?

Just because something followed something doesn’t necessarily mean the first something caused the second something. Some of my not particularly card-carrying conservationist friends in Ashland have ventured to say to me that the smoke is worse these years because logging on federal public lands is now a lot less than in past decades—a notion offered up by the timber industry at every chance. Of course, to Big Timber, it’s just an excuse to resume abusive logging on the nation’s federal public lands.

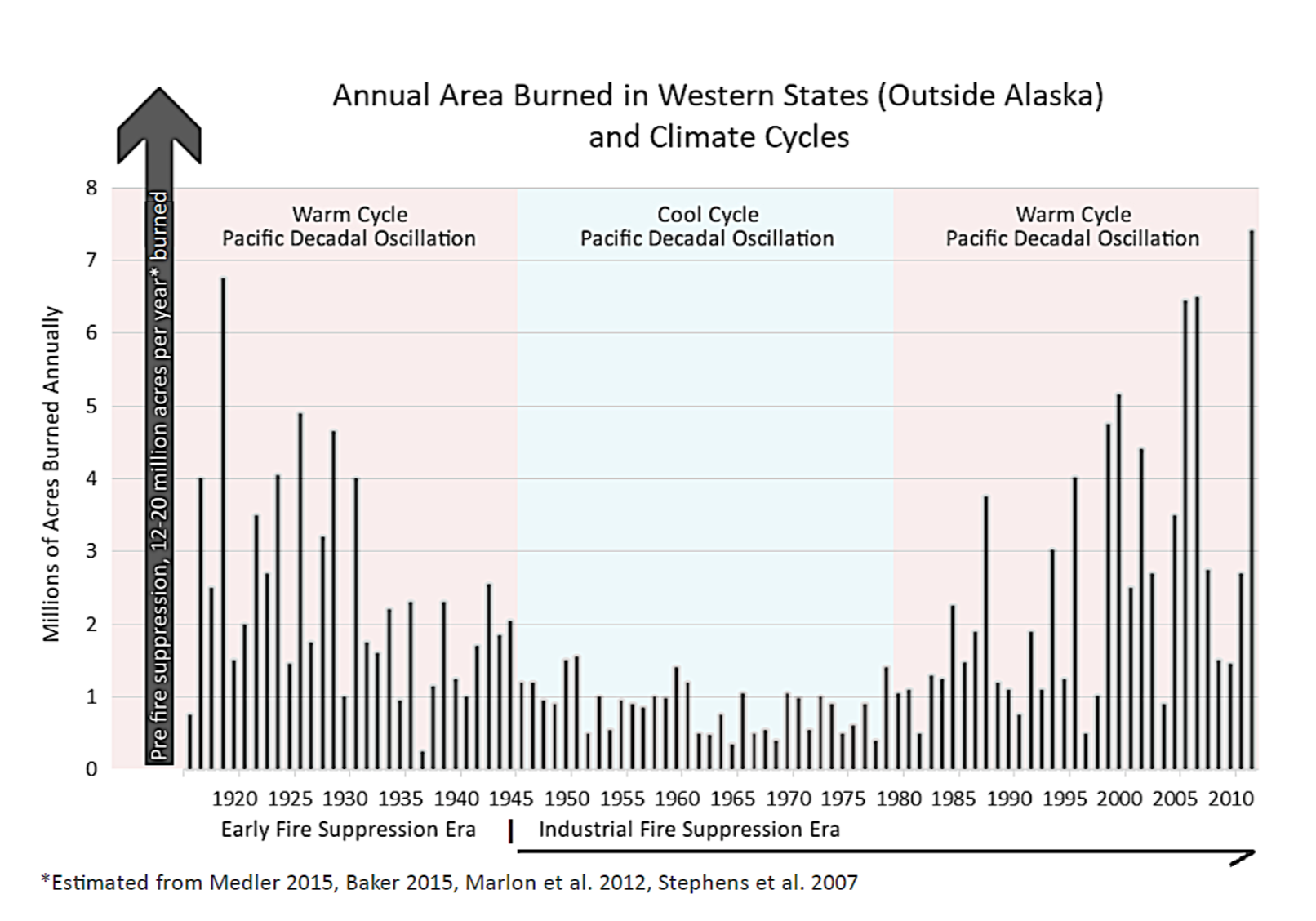

I patiently (at least I think I’m patient) explain that we are both in the hotter end of a long-term weather cycle and that climate change that is warming the forest is making the fires more frequent and more intense. Everyone’s personal reference point is what one grew up with, and when I grew up, there were not as many forest fires. Those who remembered the great fires prior to World War II are mostly dead now. I came of age in a cool cycle (Figure 2). I thought it was because the government was successfully suppressing fires, but it was mostly about the weather. I should start carrying a laminated copy of Figure 2 in my pocket to aid conversation.

Figure 2. Yes, more acres are burning, but only compared to the period from the death of Franklin Roosevelt to the election of Ronald Reagan (memorable events that had nothing to do with fire). Source: Dominick DellaSala, Geos Institute.

I also try to work into the conversation a few other relevant facts, such as these:

•Inversions happen. The Rogue Basin has a lot of episodes where cooler air near the ground is trapped beneath warmer air. Air pollution is not mixed with the upper atmosphere and doesn’t go away. That trapped pollution may be locally produced by local fires, automobiles, factories, or woodstoves or may come from forest fires as far away as British Columbia. Any particulates that pass by the Rogue Basin during an inversion actually stay.

• Automobiles, factories, and woodstoves contribute. Locally produced pollution is a chronic and generally constant source of air pollution and is harmful as well. It would be more effective to reduce these sources than try to stop forest fires.

• Most fires are human-caused. Nature can start wildfires either by lightning or lava, but as many as 90 percent of wildfires nationally are caused by humans, usually by unattended campfires, burning debris, flicked cigarettes, or arson.

• Many forests are fire-dependent. A forest fire is either the rebirth or the continuation of the forest. I wish I had said what assistant professor of disaster and emergency management Eric Kennedy of Toronto’s York University said: “Forests and fires are as inseparable as oceans and waves. No matter what management strategies we use, wildfires will always occur.” Complaining about forest fires is as useful as complaining about the weather or gravity.

What to Do About the Smoke

The conversation usually concludes with my interlocutor(s) asking what can be done to reduce smoke in the Rogue Basin. To make a dent, one could clear-cut all the forests and haul every bit to the mill and then periodically spray the land with herbicides so the forests don’t grow back and burn again. As forest fire smoke can travel a long way, one would have to treat all forests this way to make a dent in the smoke. A similar treatment would be necessary to prevent those fires in the wheat fields of north central Oregon that also affect air quality in the Rogue Basin.

The timber industrial complex’s solution is to “thin” the forests. Big Timber uses the term thinningrather than loggingor clear-cuttingto describe their hopes. However, their thinning of a forest is not akin to thinning a row of carrots in a garden. To thin a forest enough so that the forest will not burn, one would have to thin the trees to such a wide spacing that the landscape would be a savannah, not a forest.

Those solutions are what not to do. Here is what I suggest society should do (in no particular order of importance):

• Ban woodstoves. Though the particulate pollution during the woodstove season is generally countercyclical to the fire (smoke) season, even the best woodstoves still pollute unacceptably and are a source of particulate pollution. We can help our health in the winter by not burning wood even though in the summer we cannot help wood not burn.

• Set prescribed fires. Not small and occasionally like now, but large and frequently. Burn when inversions are not happening.

• Widen the window for prescribed fires. The smoke from a wildfire—be it started by nature or a human—doesn’t violate air quality standards. The rules do apply to smoke from prescribed fires. Such burning is allowed only when the chances of smoke intruding into town are essentially nil. The problem is compounded by risk-adverse land managers who will only set a forest afire when the moisture (both air and fuel) conditions are just right and they are confident that their small burning crew can prevent any burning outside the prescription. The fire-industrial complex needs to allocate resources for prescribed burning as it does for wildfires.

• Reduce pollution from motor vehicles, industry, and farming.Any particulate pollution—be it from a tailpipe, a smokestack, or blowing dust from bare farmland—is unhealthy. These emission sources can be better controlled, while forest fires cannot.

• Give refundable tax credits to buy HEPA filters, insulate buildings, and replace woodstoves.Such would be especially helpful to those of us at most risk from particulate pollution and would reduce health care costs. My house in Ashland doesn’t have air conditioning, as it has windows that open at night when the air is cool and close during the day when the air is hot. This comfort strategy is less viable now that we have a smoke season more years than not. There is now a large HEPA filter unit in my house that works very well in a tightly insulated space.

• Close the woods during periods of extreme fire danger.I remember the fall deer hunting seasons of my youth occasionally being disrupted by such closures in my youth. Inconvenient, but the closures resulted in fewer fires at a time when they were most unwelcome.

• Decarbonize the economy. A warming climate means a warming forest means more fires. To avoid the worst effects of climate change, we must return to an atmospheric carbon dioxide level of no more than 350 parts per million.

Adapting to Smoke Season

When the winter season comes, I either put on more clothes or head south. When the summer season comes, I either put on less clothes or head to the mountains or the beach. When the fire season comes, I either suck it up—perhaps through a quality filter—or leave. A major reason I live in the land of ash (we just call it Ashland) is that I enjoy the surrounding forests. If we are to have functioning forest ecosystems, across the landscape and over time, fire—sometimes very large and at inconvenient times—must occur.