Most wildlife species spend time on the move. Large mammals, in particular, often make long annual migrations in the course of a year. Mammals don’t fly like birds so they need safe passage on the ground.

Just as it is in the public interest to have systems of corridors for the movement of vehicles, oil, gas, electrons, and water, it is in the public interest to have a system of corridors for wildlife. Wildlife corridors are for mammals large and small that must walk to where they need to go. They are also for monarch and other butterflies that cannot fly very far at one time so need habitat closely spaced along their ways.

Figure 1. An overpass on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana is used by black and grizzly bears, deer, elk, and mountain lions. Source: Wikipedia

When anthropocentric corridors cross wildlife corridors, wildlife always loses. If the highway is not an outright impenetrable barrier, attempting to traverse the barrier often results in death or injury, as evidenced by the road kill we see everywhere along our highways. Spending too long traversing the cleared swath for power lines can result in a small mammal being picked off by a predator.

Plenty of peer-reviewed science (listed, for example, in the Conservation Corridor Publication Library and the Center for Large Landscape Conservation Library) attests to the importance of wildlife corridors. It is time for society to affirmatively protect and recreate wildlife corridors big and small, short and long, narrow and wide.

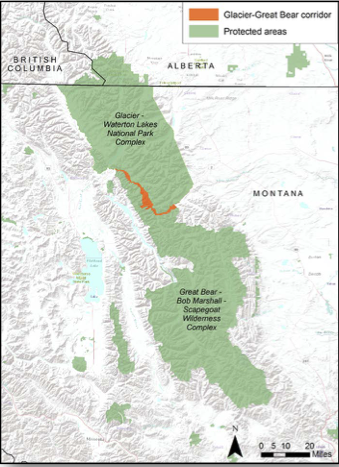

Figure 2. A national wildlife corridor designation between Glacier National Park and the Great Bear Wilderness would facilitate the building of structures to allow the migration of grizzly bears and other wildlife, now blocked by U.S. 2 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad. Source: Center for Large Landscape Conservation

The Need for a Systematic Approach

In this increasingly overpopulated world and overdeveloped landscape, wild animals will survive only if they have habitats and those habitats are well maintained and interconnected. Such can only be the result of intentional conservation; the incidental conservation of today isn’t working.

It is not enough to somewhat mitigate for wildlife while maintaining existing corridors or building new ones. For example, while significant progress has been made in providing underpasses and overpasses for wildlife as highways are upgraded (see Figure 1), wildlife will always be a low priority—an afterthought if we are lucky. Society needs a systematic approach where wildlife is not an afterthought but a beforethought and a duringthought.

Wild animals don’t care about state boundaries (nor international ones, for that matter). The federal government—as landowner, as regulator, as tax collector, and/or as grant maker—has the power to establish and encourage wildlife corridors.

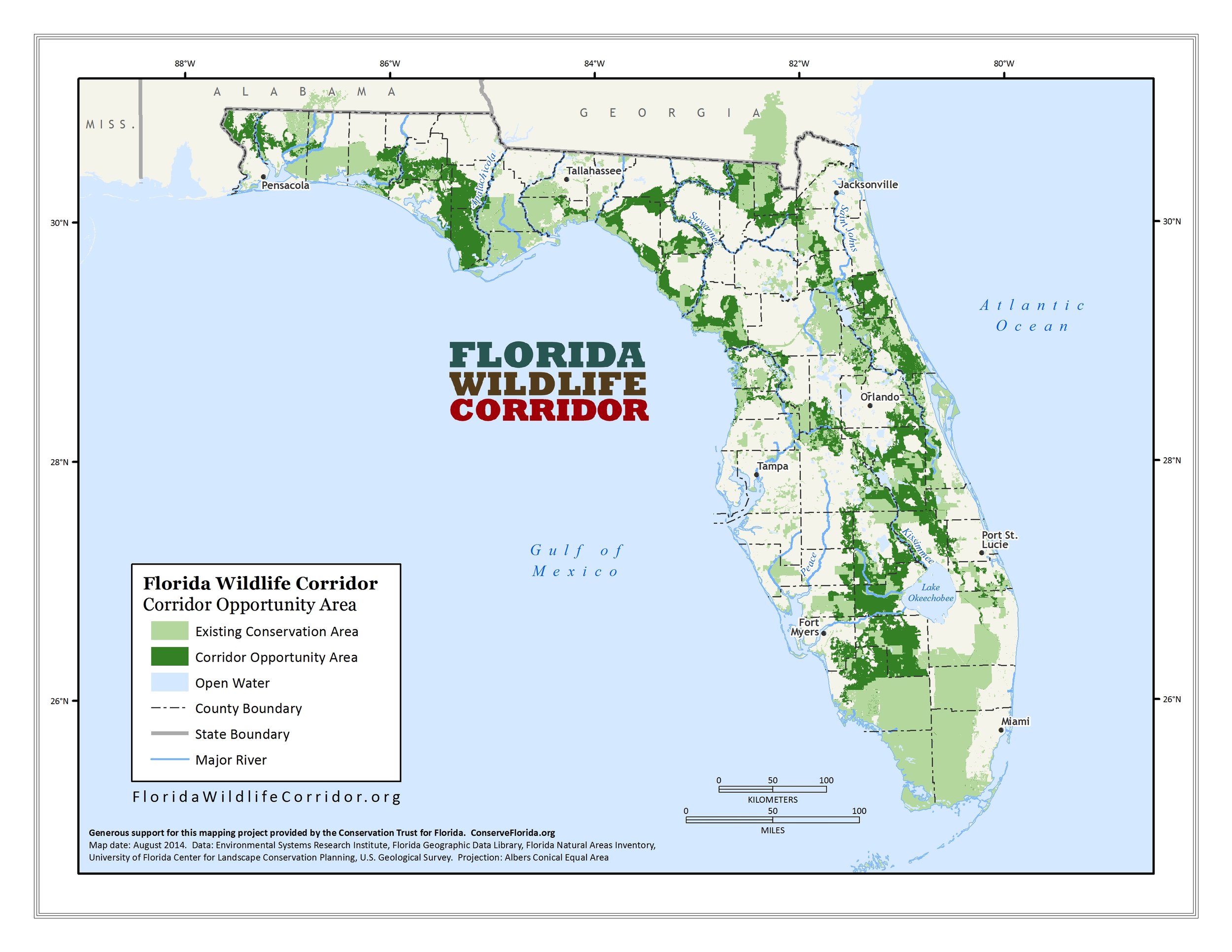

The Interstate Highway System was designed and built for the movement of people, goods, and military equipment and has served its purpose spectacularly. We need a National Wildlife Corridors System to ensure the movement of wildlife for the benefit of this and future generations (see Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Figure 3. A very large herd of pronghorn summers in and around Teton National Park and winters in the Upper Green River Valley of Wyoming. Development is impeding its migration (and rampant energy exploitation is disturbing its critical winter range). Source: Wildlife Conservation Society

The Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act

In 2010, Representative Rush Holt (D-12th-NJ) introduced the pioneering Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act of 2010. Alas, the bill went nowhere, but the seed was planted. In 2016, Representative Donald S. Beyer, Jr. (D-8th-VA), introduced the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act of 2016:

To establish the National Wildlife Corridors System to provide for the protection and restoration of native fish, wildlife, and plant species and their habitats in the United States that have been diminished by habitat loss, degradation, fragmentation, and obstructions, and for other purposes.

The 2016 bill was endorsed by the eminent Harvard University biologist E. O. Wilson and other distinguished scientists. Wilson said, “The National Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act would provide the most important step of any single piece of legislation at the present time in enlarging the nation’s protected areas and thereby saving large swaths of America’s wildlife and other fauna and flora.”

The Wildlands Network says in its six-page explanation of the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act of 2016 that this is what the bill does:

• Grants authority to key federal agencies to designate wildlife corridors, which will be managed in a way that contributes to the connectivity, persistence, resilience and adaptability of native species. Requires that Department of Interior – in consultation with the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense and Transportation and in coordination with states, tribes and others, develop a strategy for development of the corridor system.

• Requires coordination in both designation and management of corridors with other federal departments, and states, tribes, local governments, NGOs and private landowners.

• Promotes public safety and mitigates species damage where corridors cross roadways.

• Establishes the Wildlife Corridors Stewardship and Protection Fund to support the management and protection of Corridors and other lands and waters important to connectivity.

• Provides authority to acquire land and interest in land [by] using funds from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, Corridors Stewardship and Protection Fund, and private donations.

• A National Native Species Habitats and Corridors Database will be developed and freely available to the public.

• A Wildlife Corridors Stewardship and Protection Fund will be established to provide the financial resources necessary to carry out and sustain this system.

Under the bill, national wildlife corridors (NWCs) could be established by Congress by statute, by the secretaries of the five departments of government specified in the legislation by administrative rulemaking, or by federal and resource management agencies in local alnd and resource management plans. A citizen nomination process would also be possible and require consideration by the affected secretary.

Figure 4. Only about one hundred of the Florida panther still remain, so it is critical for these individuals to be able to make their way to each other to mix up their narrowed genetics and to reoccupy historic habitats. Some 9.5 million acres in the Florida Wildlife Corridor are already managed for conservation, from the Blackwater Wildlife Management Area to Everglades National Park. The 6.3 million acres that connect the existing conservation areas need to have their conservation status elevated, as national wildlife corridors would do. Source: Florida Wildlife Corridor

Hopes for the Bill Going Forward

We can hope that when the bill is reintroduced into the current Congress (2017–2018), it will include at least one Republican cosponsor. In addition, it is important that companion legislation be introduced in the Senate, which we can hope will also have cosponsors of each political party.

Though the legislation is very commendable and worth enacting into law as it is now drafted, a major weakness is that it authorizes—but does not require—the secretaries of agriculture, commerce, defense, interior, and transportation to establish national wildlife corridors (NWC). Any NWC that is actually beneficial to fish and wildlife will require modification of activities that these departments often view as their main mission. Bureaucracies, as a class, never favor laws that require them to change their behavior.

In addition to hoping that the language can be strengthened, I recommend four improvements to future versions of the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act:

1. Give federal tax breaks to private landowners within a designated NWC who agree to manage their land in ways compatible with wildlife and helpful to wildlife migration.

2. Direct that licenses issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission that affect lands within an NWC be issued only if they are compatible with the purposes of an NWC.

3. Prevent the expenditure of federal funds on activities in NWCs that are inconsistent with an NWC, similar to what is stipulated for the Coastal Barriers Resources System.

4. Require federal agencies to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure that their activities in NWCs are compatible.

What You Can Do

Conservation organizations are increasingly focused on wildlife corridors. Nearly fifty such organizations have endorsed Representative Beyer’s 2016 legislation. Make sure your favorite conservation organization keeps wildlife corridors in mind. Several major conservation organizations have joined together in the Connectivity Policy Coalition, coordinated by the Wildlands Network and the Center for Large Landscape Conservation.

You should also contact your congressional delegation (two US senators and one member of Congress) about the importance of wildlife corridors. Ask them to cosponsor the National Wildlife Corridors Act.