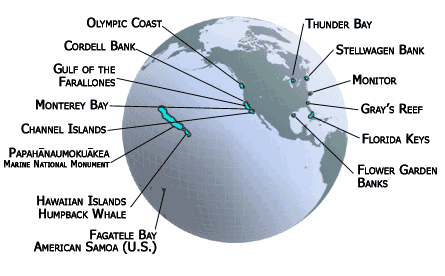

The National Marine Sanctuary System as of 2017.

In April 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13795, which among other things is designed to promote oceanic oil and gas exploitation. The order requires the secretary of commerce to

refrain from designating or expanding any National Marine Sanctuary [NMS] . . . unless . . . the expansion proposal includes a timely, full accounting . . . of any energy or mineral resource potential within the designated area—including offshore energy from wind, oil, natural gas, methane hydrates, and any other sources . . . deemed appropriate—and the potential impact the proposed designation or expansion will have on the development of those resources.

Further, the secretary of commerce, within 180 days, in consultation with the secretaries of defense, interior, and homeland security, shall conduct a “review” of all NMSs. The review is to consider an analysis of budgetary impacts of NMS management; the adequacy of required federal, state, and tribal consultations before designation; and the “opportunity costs associated with potential energy and mineral” exploitation.

Notice that there is no requirement to review the economic benefits of NMS designation, which include ecosystem goods and services (several of which can be quantified in dollars) and avoided climate change due to keeping fossil fuels safely in the ground.

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act of 1972, as Amended

In 1972 Congress enacted the National Marine Sanctuaries Act (NMSA). Since then the statute has been amended and reauthorized six times, each being a generally weaker incarnation of the former. As first conceived in the wake of the first Earth Day in 1970, national marine sanctuaries (NMSs) would be the oceanic analogue of national parks and wilderness areas. But by the time Congress enacted the National Marine Sanctuary System (NMSS) into law, it was a multiple-use—not a preservation—statute. An onshore analogue of an NMS is a national forest in the National Forest System.

NMSs have been established to protect shipwrecks, whales, coral reefs, and other things marinely spectacular. “Sanctuary” is generally a misnomer, though, in that NMSs are not true sanctuaries from all extractive uses. Most NMSs were established by the secretary of commerce in the process mandated in the NMSA. Surviving this process means that most NMSs come out the other end of the bureaucratic meat grinder as compromised. While oil and gas exploitation is generally banned (sometimes NOAA doesn’t do so, but Congress always steps in and does so ban), other extractive uses are often not.

In fact, NMSs are managed for multiple uses, as long as those uses are deemed compatible with the purposes of an NMS. In fact, in an NMS, no use is expressly forbidden by statute, but rather it is the secretary of commerce, through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who decides what’s allowed or not. Extractive uses, such as fishing, can be regulated or—if politically possible and ecologically necessary—prohibited. NOAA, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, includes the National Ocean Service (NOS), the low-profile federal agency entrusted with the administration of NMSs.

The Scope and Size of National Marine Sanctuaries

The thirteen NMSs are found in U.S. waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Great Lakes. The sanctuaries range in size from the 1 square nautical mile surrounding the sunken U.S.S. Monitor off of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to the 13,581 square nautical miles in the American Samoa NMS. In 2017, the National Marine Sanctuary System encompassed 620,692 square nautical miles (~526 million acres), though actual NMSs constituted only 38,118 square nautical miles (~32.3 million acres).

That’s because the NOAA Office of Marine Sanctuaries considers the enormous Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (582,574 square nautical miles) a part of the National Marine Sanctuary System, although it is not technically a national marine sanctuary. Some NOAA maps depict Papahānaumokuākea as a national marine sanctuary, but the official paperwork (the stautorily defined process) for it to be established as a national marine sanctuary by the secretary of commerce has not been completed, nor has Congress established it as an NMS, another path to NMS designation. The process to establish a Northwest Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary was initiated by the Clinton administration. However, in 2006, President G. W. Bush used authority granted by Congress to establish the Northwest Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary. In 2007, renamed it the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

The NOAA Office of Marine Sanctuaries serves as trustee for both the Papahānaumokuākea and the Rose Atoll marine national monuments. The two marine national monuments are “jointly managed” with the US Department of the Interior (operationally, either the National Park Service and/or the Fish and Wildlife Service). The Rose Atoll Marine National Monument is now fully encompassed in a larger American Samoa NMS.

Finally, and ironically, these three marine national monuments are not in the National Marine Sanctuary System:

· Northeast Canyons and Seamounts (4,193 square nautical miles)

· Marianas Trench (95,216 square nautical miles)

· Pacific Remote Islands (395,204 square nautical miles)

Together, these three amount to a total of 494,613 square nautical miles (419.2 million acres) of sanctuaries for marine life. The primary jurisdiction for these marine national monuments is the Interior Department, not the Commerce Department (NOAA).

The Policy and Politics of National Marine Sanctuaries

There are a number of significant flaws in the way NOAA establishes and administers marine national monuments:

· Scope and scale. The need is for very large marine protected areas, something that is nigh impossible to convince a bureaucratic agency of, even during a presidential administration generally sympathetic to marine conservation.

· Weak statutory mandate. Getting a part of the ocean established as a national marine sanctuary through the administrative process is useful, but not sufficient, conservation. Congress needs to strengthen the conservation mandate for NMSs.

· Hamstrung bureaucracy. Not that most bureaucracies are not so encumbered, but history has shown over the nearly half a century since the NMSA was first passed that the congressionally mandated process for administrative establishment doesn’t meet the societal need. Even though the decision is being made by the secretary of commerce, staffed by a bureaucracy in usually faraway Washington, DC, only NMS proposals with near-unanimous local support generally make it through the process.

If you want to go deep into the good, the bad, and the ugly (and how to fix it), an excellent critique of national marine sanctuaries is the decade-old master’s thesis by William J. Chandler (then with the Marine Conservation Institute) entitled The Future of the National Marine Sanctuaries Act in the Twenty-First Century.

As far as the politics go, the energy and fishing industries are always and generally hostile, respectively, to the establishment of NMSs.

While not statutorily the case, by policy no energy exploitation is allowed in NMSs. The general idea is to conserve the areas in a natural state. The conflict is irreconcilable.

NMSs often have zones that limit or prohibit fishing in order to protect fish, other species, and/or ecosystem values. Fishing interests can generally be categorized as either commercial or recreational. Past and current overfishing has resulted in increased regulation (including, but not limited to catch limits, size limits, gear limits, season limits, by-catch limits, and participant limits). Most fishing interests feel they have enough regulation and see NMSs as just more burdensome government mandates.

Bypass the Bureaucracy by Going to Congress

A more effective approach might be to seek NMS designation directly from Congress. Of course, local politics can also come into play as with the bureaucratic process, but I think the odds of strong conservation are better in the end.

Believing the NMS bureaucracy is out of control (in my dreams), Rep. Don Young (R-AK) has introduced H.R. 222 (115th Congress) “[t]o amend the National Marine Sanctuaries Act to prescribe an additional requirement for the designation of marine sanctuaries off the coast of Alaska, and for other purposes.” The bill would fix things so that the secretary of commerce cannot proclaim any national marine sanctuary off the shores of Alaska unless an Act of Congress says she can and also specifies the actual map.

Bypass Congress by Going to the (Right) President

Congress has not reauthorized or amended the NMSA since 2000. Now would not be a good time to try. Recent history, under both a Republican and a Democratic president, has shown that serious large-scale ocean conservation occurs only with the use of the Antiquities Act.

Through the Antiquities Act of 1906, as never amended, Congress granted the president the authority to “declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated on land owned or controlled by the Federal Government to be national monuments.” From the edge of state waters (in most cases 3 nautical miles from the coast) to the extent of the territorial sea, the United States has full sovereign control of ocean “land.” Extending 200 nautical miles from shore is the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (USEEEZ) that is “controlled by the federal government.”

Potential National Marine Sanctuaries

The Obama administration actively sought nominations for new NMSs for the first time in more than two decades, with mixed results.

Two new NMSs are pending:

· Mallows Bay-Potomac River (Atlantic [MD])

· Lake Michigan (Great Lakes [WI])

They were nominated by the states of Maryland and Wisconsin respectively. However, public comment was completed after Obama left office, so it is up to the Trump administration to decide on final official establishment. Time will tell whether this administration finishes the job or finishes them off.

The following areas are on NOAA’s inventory of successful nominations:

· Chumash Heritage (Pacific [CA]; second submission)

· Lake Erie Quadrangle (Great Lakes [PA])

· St. George Unangan Heritage (Pacific [AK])

· Hudson Canyon (Atlantic [NY])

· Mariana Trench (Pacific [CNMI])

· Lake Ontario (Great Lakes [NY])

CNMI? Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands, of course. (Yes, I had to look it up.)

Two applicants withdrew their applications:

· Eubalaena Oculina (Atlantic [FL]; second submission)

· Baltimore Canyon Urban (Atlantic [MD])

NOAA rejected these nominations:

· Eubalaena Oculina (Atlantic [FL]; first submission)

· Aleutian Islands (Pacific [AK])

· Chumash Heritage (Pacific [CA]; first submission)

Now under review is this nomination:

· Southern California Banks (Pacific [CA])

Offshore Oregon

I have previously suggested a large marine protected area off the shores of Oregon in the form of a marine national monument. It could also be in the form of a national marine sanctuary, but likely only if done directly by Congress and including a strong conservation mandate to protect, conserve, and restore for this and future generations.

There are many offshore Oregon sites worthy of federally protected status, including but not limited to these:

· Gorda Ridge, in the USEEZ in the eastern Pacific Ocean off southern Oregon and northern California, encompassing undersea volcanoes, thermal vents, and newly discovered life forms.

· Astoria Canyon and Fan, offshore from the mouth of the Columbia River, shaped by the massive Missoula Floods seventeen thousand years ago.

· Heceta Bank, Perpetua Bank, and Stonewall Bank, 15 to 30 nm off the central Oregon coast, where underwater seamounts 10 by 25 nm in area and 30 to 60 fathoms (180 to 360 feet) below the surface cause upwelling that provides food for lots of seabirds. Of this area, 800,027 acres have been designated an Important Bird Area by the National Audubon Society.

These state-protected areas are worthy of overlapping federal protection as well:

There are more areas I’ve not included.

An Offshore Oregon National Marine Sanctuary must have a combination of marine strictly protected areas (no extraction) as well as a multiple-use mandate limited to the sustainable uses of renewable resources (no mining, no drilling, and so on).

Offshore Washington is the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Offshore California are several national marine sanctuaries with more in the works. Offshore Oregon is missing in action. Source: NOAA National Marine Sanctuaries Program.