Preremembering James Monteith, Oregon Conservationist

Top Line: Countless Oregon roadless areas, old-growth forests, and free-flowing streams have not been roaded, clear-cut, and/or dammed thanks to James Monteith.

Figure 1. Left to right: Gayle Landt, James Monteith (check out his free-flowing mane), Kurt Kutay, and Marcy Willow (all standing), early staff members of the Oregon Wilderness Coalition (OWC), ca. 1974. Joe Walicki (squatting) was one of the three founders of OWC. Source: Joe Walicki.

Much of Oregon’s wild forest land that is safely in the National Wilderness Preservation System today would have been roaded and clear-cut if not for legendary Oregon conservationist James Monteith. While many righteous local heroes deserve credit for saving these Oregon forest roadless areas for the benefit of that and future generations, the overarching hero was Monteith.

It is my wont to remember noted Oregon public lands conservationists while they may still, I hope, enjoy what I have to say about them. I have done such preremembrances of Oregon conservationists Mary Gautreaux, Jerry Franklin and Norm Johnson, Jim Weaver, Brock Evans, Bob Packwood, Norma Paulus, and Barbara Roberts. Now it’s Monteith’s turn.

Firmly in his mid-seventies and living in his beloved Wallowa County with his beloved wife, Nancy E. Duhnkrack, Monteith is still making a difference in re the conservation of his native state’s lands and waters, but now in more localized ways.

Organizing to Meet the Challenge and Move the Needle

In the early 1970s, three Oregon conservationists came together to found the Oregon Wilderness Coalition (OWC). Holly Jones and Bob Wazeka, then super-active Sierra Club volunteers from Eugene, and Joe Walicki, then Northwest representative for The Wilderness Society, envisioned a network of local wilderness advocacy groups across Oregon, especially in places where the Sierra Club name was not an asset (bumper sticker du jour: “Sierra Club: Kiss My Axe”).

The articles of incorporation for OWC called for “a full-time staff person” to advocate for wilderness in Oregon. Fred H. Swanson was that initial staffer, but soon James Monteith assumed command. Monteith came to the cause of Oregon wild lands and waters via a circuitous route that took him from being the student body president at Klamath (Falls) Union High School to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and then to Stanford University and to studying wolves in Fairbanks. A mezcal-induced vision on a Mexican beach brought him back to Oregon, where he talked himself into the OWC job. James served as executive director of OWC from 1974 to 1991, with the organization changing its name to Oregon Natural Resources Council (ONRC) in 1982. (Later, in 2006, ONRC became Oregon Wild.) My association with James began in 1975 during the lead-up to the Endangered American Wilderness Act of 1978.

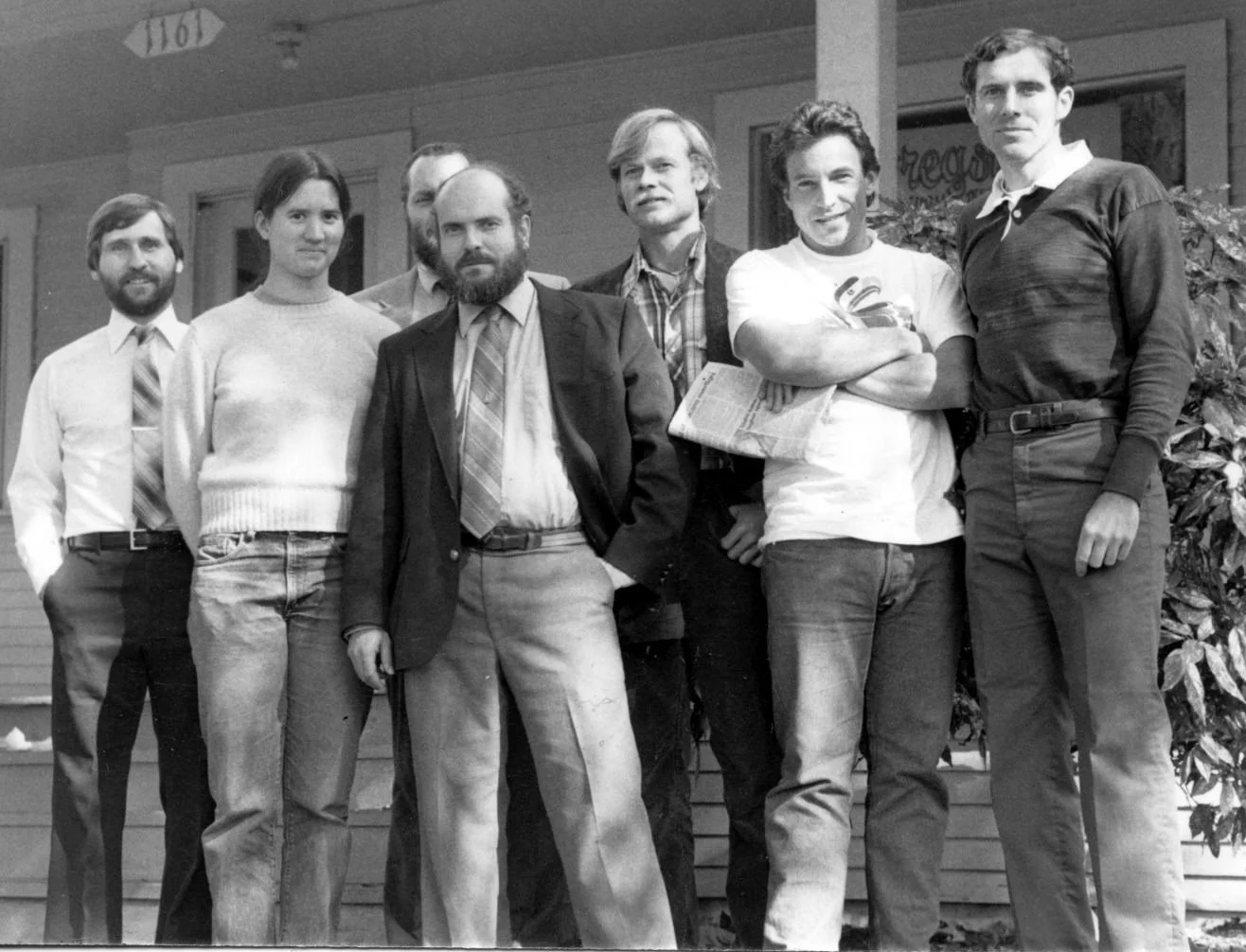

Figure 2. Oregon Wilderness Coalition staff, ca. late 1970s. Clockwise from top left: Tim Lillebo, Kurt Kutay, Nancy Duhnkrack, Andy Kerr, and James Monteith.

Besides me, other early planets in the Monteith orbit were the likes of Kurt Kutay, Tim Lillebo, Nancy Duhnkrack, Nancy Peterson, and Don Tryon. Soon came along Wendell Wood. In overlapping orbit were close comrades like Randal O’Toole and Cameron La Follette. Scores of others happily succumbed to Monteithian gravity over the years, pausing or redirecting their lives to go all out for Oregon’s wild lands and waters. (It also really helped that the economy was in the toilet during the Carter administration, 1977–1981, and nonprofit organizations could get federal money to hire people.)

Figure 3. Oregon Natural Resources Council staff in the early 1980s. Left to right: Mark Prevost, Nancy Peterson, Andy Kerr, Wendell Wood, Tim Lillebo, James Monteith, and Don Tryon. Source: Oregon Wild.

Tales of the Early Monteith Era

OWC staff (plural) began as a few nature zealots in need of stationery, who then also needed an office. Where the University of Oregon Law School now stands, across from Hayward Field, were a few dozen 320-square-foot former married-student housing units. They started their lives on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation helping create the atom bomb, but were snapped up by a university with a severe shortage of housing after World War II. By the late 1970s, the Agate (Street) shacks could be had by any program or department at the UO, and Monteith surreptitiously gained control of about a half-dozen of them. Each shack came with a heater, a telephone line, and a bathroom. All “free” from the unknowing university.

During the leanest of those times, Monteith slept in his office. (Hell, he worked all the time anyway.) Somehow, he arranged to shower at a nearby women’s dorm . . . ;-)

These were the first offices of the Oregon Wilderness Coalition. Once a year the university’s contracted IBM typewriter repair person would come by to service the machine owned byOWC, not the university. If the tech noticed that he didn’t have the serial number on file, Monteith could usually sweet-talk him into servicing it anyway.

We were also using the university phone system, and Monteith could occasionally sweet-talk a UO operator into letting him make calls on the state WATS (wide area telephone service) line. Back in the day before email and the internet, it was expensive to make long-distance calls. The UO phone system was linked with other state university phone systems as well as state offices in Salem. I eventually figured out that by dialing the correct ten digits before the ten-digit number we wanted to call—with just enough pauses to allow the switching to work—one could sit in Eugene and call anywhere in the country using State of Oregon lines from Salem, after first going through the Oregon State University phone system. At the time, I guestimated the free rent, utilities, and phone service (and typewriter maintenance) to be worth well over $100,000 per year, which was a lot of money back then (~$0.55 million in today’s dollars).

One of Monteith’s great strengths was his ability to gather support for nature warriors. When he first found me in 1975, I was on a slow-motion dropout trajectory at Oregon State University in Corvallis. In the summer of 1976, Monteith and Kurt Kutay each generously waived $50 (equivalent to ~$290 in 2025) of his ~$400/month salary (a self-imposed 13-percent pay cut) so Tim Lillebo and I could turn pro. That fall I scored an Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group internship that paid $200/month. I was still living with my parents at the time (awkward). My father was not impressed with my 300-percent raise in salary!

In 1977, James and I and some others were invited to a dinner at a pretentious (pronounced “expensive”) restaurant on 7th Street in Eugene (“Would you like a salad before your entrée?”), hosted by Representative Jim Weaver. OWC didn’t have the money for us to attend, but one of us had a credit card with some room on it, so we went. It was a great dinner, where the conversation and liquor flowed freely. Fortunately, as dinner was ending, the guest of honor, Representative John Seiberling of Ohio, who chaired the relevant subcommittee of jurisdiction in the House of Representatives, tossed his credit card on the table to pay half and challenged Weaver to put the other half on his congressional expense account. It wasn’t obvious (like we had ordered bread and water for dinner), but Saint John intuited our plight that evening.

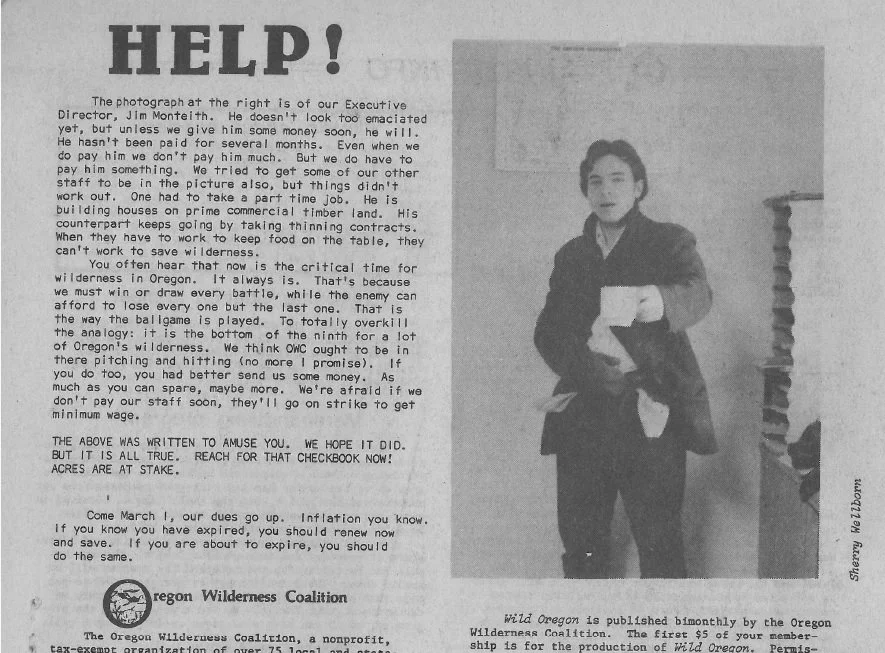

OWC/ONRC was always broke. James would joke that we were sacrificing our teeth for the cause, as the organization provided no health insurance or retirement plan, and we had no money for dentists.. At one point, the executive committee fired James and the rest of the staff. A coup ensued, the executive committee was replaced, and the staff was rehired. (All of the debt was “internal” anyway, meaning it was all unreimbursed staff expenses.)

Figure 4. A plea for donations, ca. 1980. Money was always tight, and we would do almost anything to make a buck. Source: Oregon Wild.

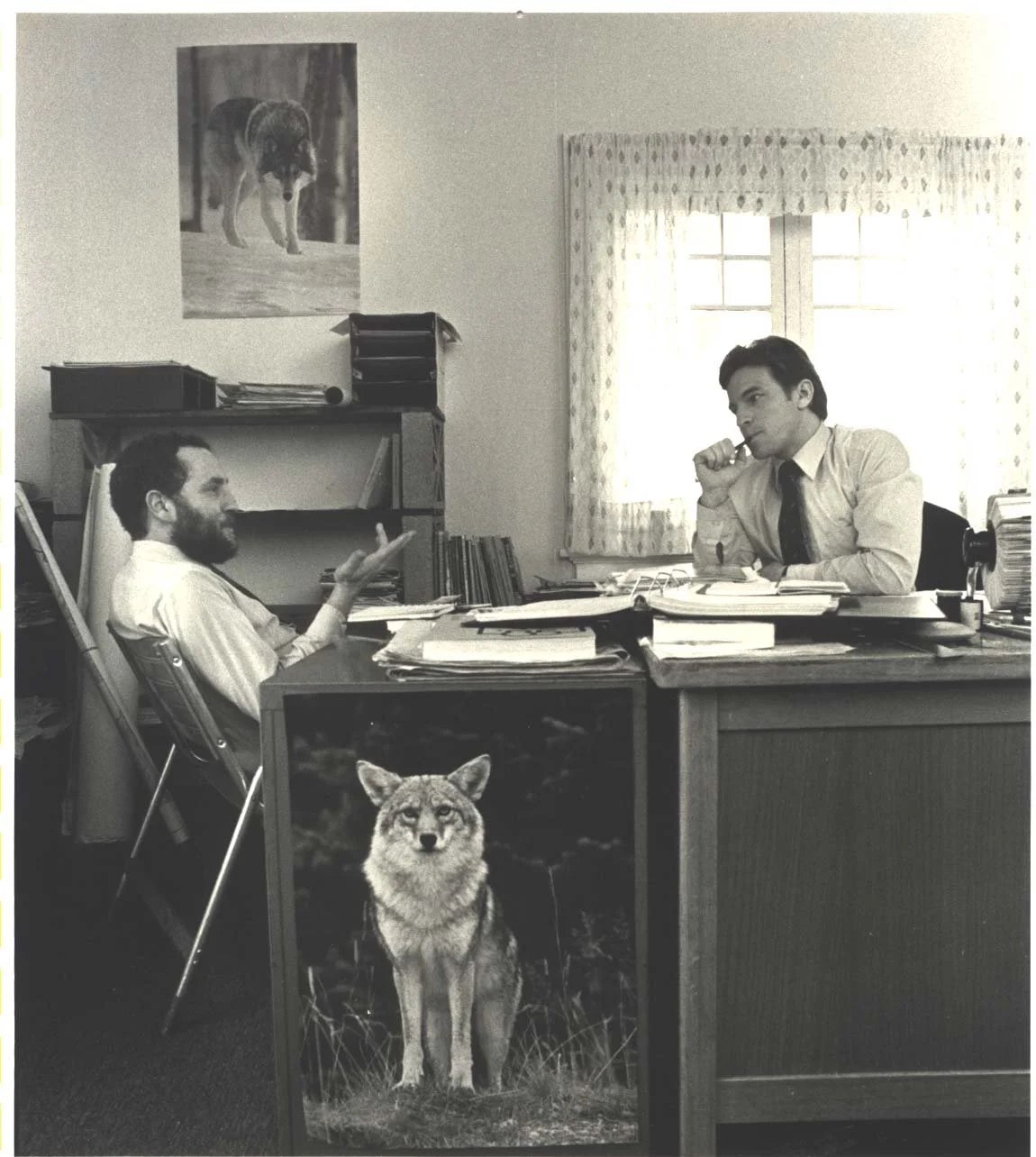

By the early 1980s, we were not the only activists leeching off the UO. Some anti-environmental (they would say pro-business) activists, who were similarly leeching off and ensconced in the UO Business School, were slowly figuring out our racket. Fortunately, a benefactor, the unforgettable Michael Horton, gave ONRC an office downtown (and off campus!).

Figure 5. James Monteith and Andy Kerr in the ONRC office on 12th Street in Eugene in the early 1980s. Source: Oregon Wild.

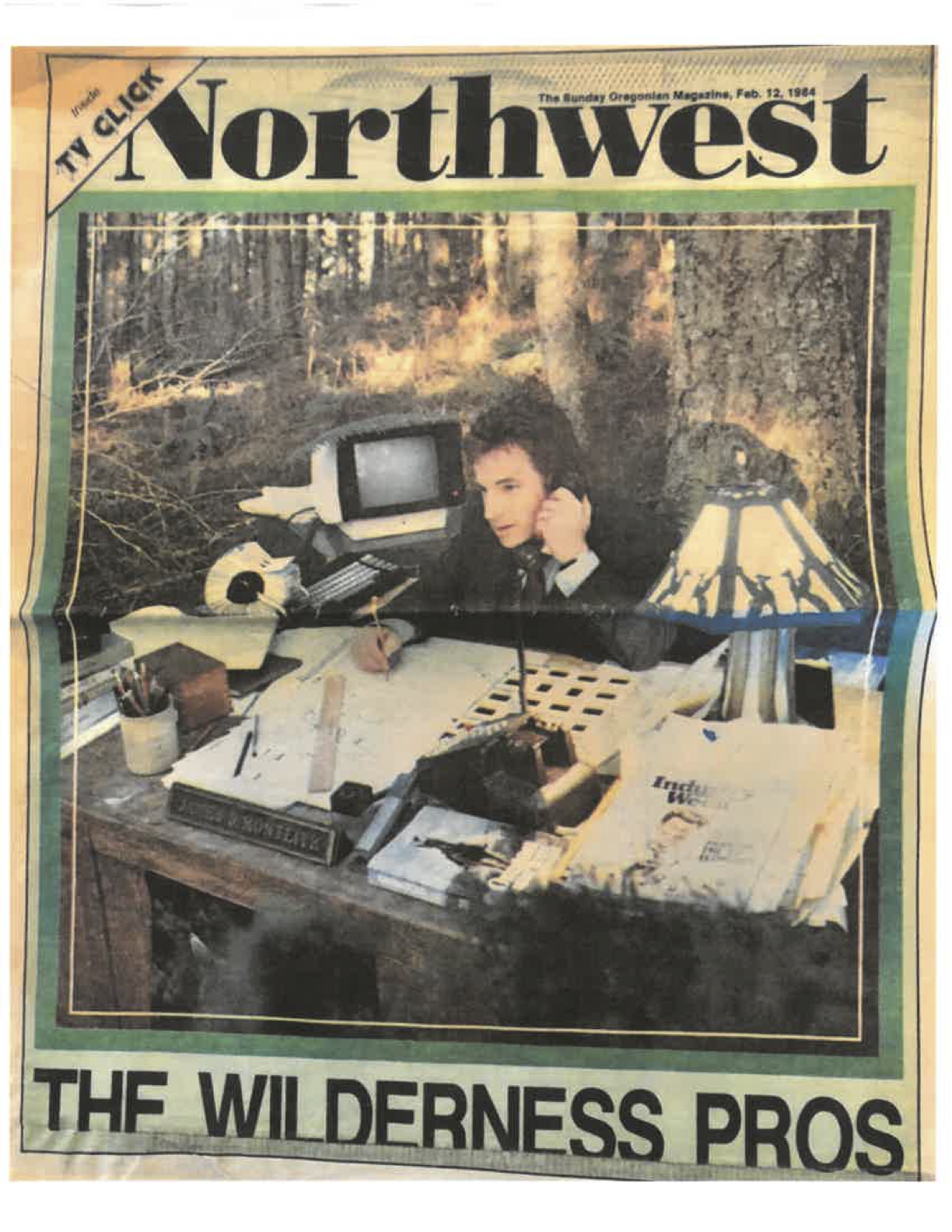

In 1984, Northwest magazine (a supplement to the Sunday Oregonian) said of ONRC, “They traded their jeans for three-piece suits and scrubbed their catchy slogans for savvy economic analysis. They’re a brand new breed of conservationist.” About that three-piece suit (singular). My mother bought it for me, but that one suit adorned by turns my, Monteith’s, and Lillebo’s frames at various congressional hearings.

Figure 6. The February 12, 1984, cover of Northwest magazine, then a Sunday supplement to the Oregonian. The Oregon Wilderness Act would be enacted into law a few months later. (Yes, James is wearing my three-piece suit.) Source: Oregon Wild.

Northwest magazine noted that “the driving force behind the council is Monteith, its chief spokesman, representing the new breed of conservationist on the Oregon political scene.” A wildlife biologist by inclination, Monteith had traded in his ponytail to become what the magazine described as a “clean-shaven, soft-spoken 34-year-old who looks like a rising corporate lawyer.” Also atypical for your average conservationist, Monteith was a hunter and a Republican, and he reached out to Native American Tribes to support wilderness designations.

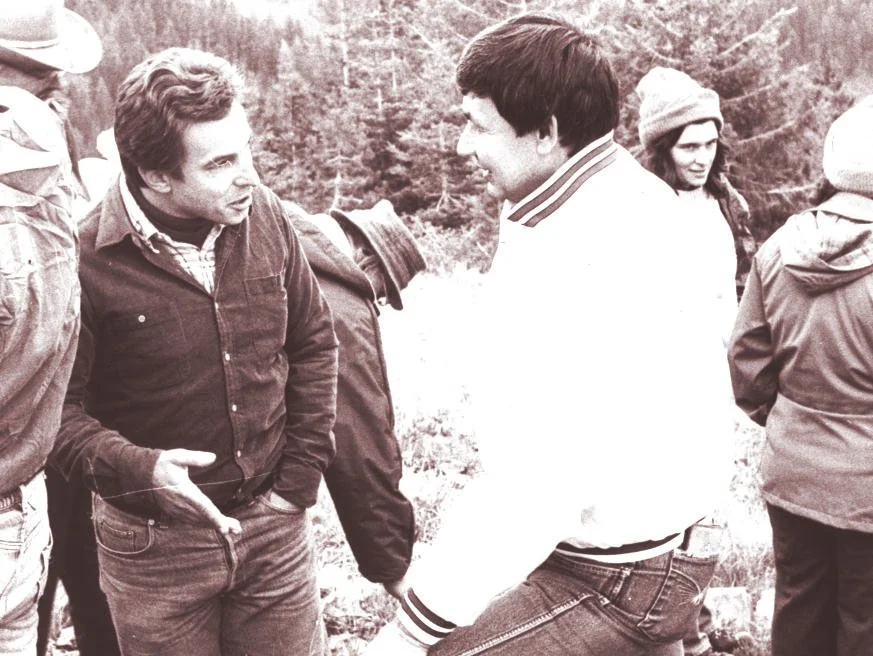

Figure 7. James Monteith and Tim Wapato of the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission.

Conservation Accomplishments and Themes of the Monteith Era

ONRC’s new breed of conservationism under Monteith’s guidance paid off with the passage of the Endangered American Wilderness Act of 1978. For Oregon, that successful legislation resulted in (1) French Pete being put in her rightful place in the Three Sisters Wilderness, (2) the Kalmiopsis Wilderness expanding northward to include some old-growth forests, (3) the ponderosa pine old-growth forest in the Wenaha River watershed being saved by wilderness designation, and (4) the Wild Rogue Wilderness (one of the first two wilderness areas on Bureau of Land Management holdings) being established.

Initially, the battle cry and bumper sticker “Save French Pete” referred to ~20,000 acres of mature (not actually a lot of old-growth) low-elevation forest, a portion of which had been excluded from the Three Sisters Wilderness when it was administratively established in 1957 (before the Wilderness Act of 1964). Actually, the de facto roadless area also included Rebel and Walker Creeks and other watersheds that totaled ~53,000 acres. In 1977, the original French Pete advocates would have been happy with just the French Pete Creek watershed, but Monteith insisted that—especially as we were now winning the battle—we could define “saving French Pete” as saving the entire roadless area, which is what was added to the Three Sisters Wilderness.

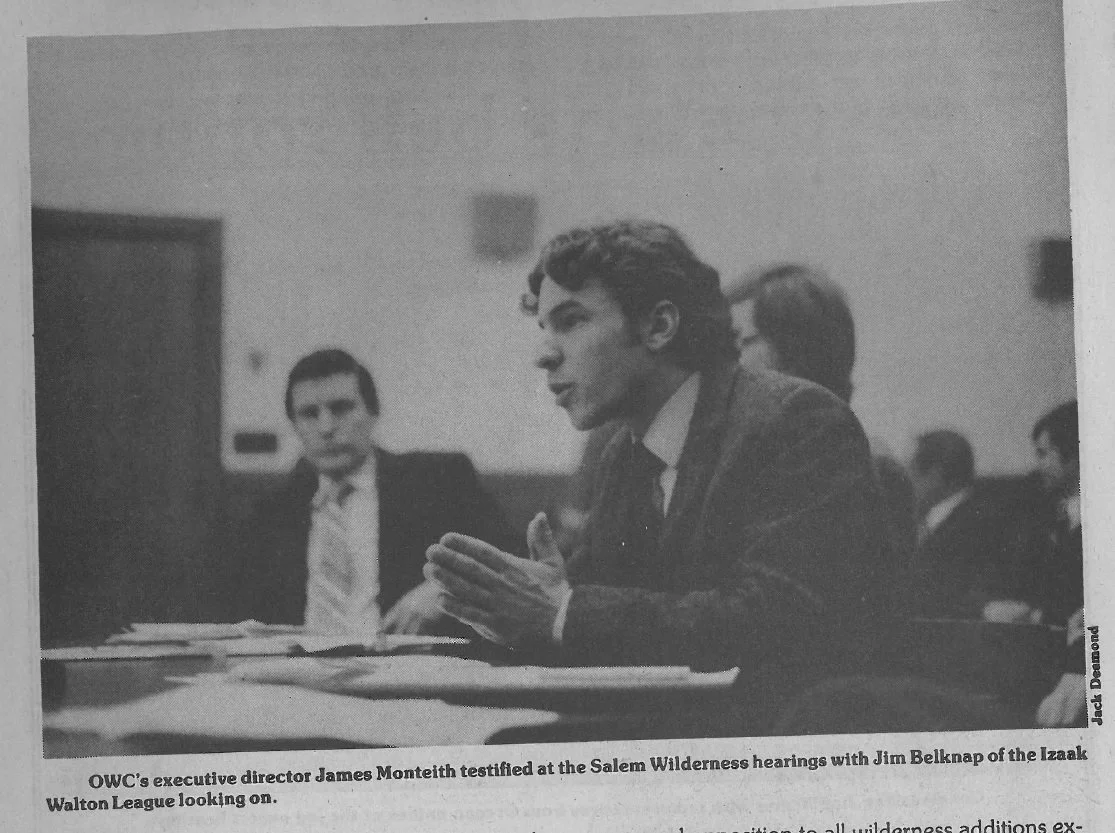

Figure 8. Monteith testifying in Salem, Oregon, in 1981 at a congressional field hearing on Oregon wilderness legislation. Source: Oregon Wild.

Most wilderness areas designated in Oregon prior to 1984 were classic “rock and ice”: above timberline or in watersheds with mostly high-elevation noncommercial forest with relatively small trees. What was most remarkable about the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 was that it protected a significant amount of rare low-elevation old-growth forests—forests that Big Timber and the Forest Service very much wanted to road and log. Timber sales were being laid out—some even were being marked with blue paint—in imperiled stands that today are within wilderness areas such as these (and several more):

• Drift Creek (Siuslaw National Forest)

• Boulder Creek (Umpqua NF)

• Grassy Knob (Siskiyou NF)

• Middle Santiam and Waldo Lake (Willamette NF)

• North Fork Umatilla and North Fork John Day (Umatilla NF)

• Mill Creek and Bridge Creek (Ochoco NF)

• Badger Creek, Bull-of-the-Woods, Salmon-Huckleberry (Mount Hood NF)

• Strawberry Mountain Wilderness Additions (Malheur NF)

Figure 9. Monteith in 1985 at Buckhorn on the western edge of Hells Canyon, celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Hells Canyon Act of 1975 by presenting the legislation’s chief sponsor, Senator Bob Packwood, with a commemorative picture. (Monteith’s long hair had long been sacrificed to the cause of wilderness.) Source: Oregon Wild.

The Endangered American and Oregon Wilderness Acts would have been enough to make Monteith’s legacy tremendous, but it was also during the Monteith Era that the battle was first joined to halt the logging of mature and old-growth forests and also stop the damming or other degradation of free-flowing streams. Under Monteith’s 1.7 decades of leadership, three overarching public lands conservation themes were conceived and advanced:

1. Wilderness is more than just recreation and more than just rock and ice.

Big Timber was trying to portray wilderness advocates as elite backpackers (some, but far from all, were), so it was important to move the wilderness debate to acknowledge not only hiking and backpacking but also hunting, birding, fishing, and more as forms of recreation. (I prefer to pronounce it “RE-creation.”) More important, while recreation in wilderness is a fine thing, it was critical to make the case for wilderness based on watershed (both water quantity and water quality), wildlife, ecological, and other values. Wilderness is important even if no one ever sets foot in the area. (I believe that the Cummins and Rock Creek Wildernesses in the Oregon Coast Range, established in 1984, were the first Forest Service wilderness areas designated by Congress that did not have even one foot of official hiking trail within them. Cummins and Rock Creek were not designated for their recreation value but for their low-elevation old-growth Sitka spruce forests and wild salmon runs.)

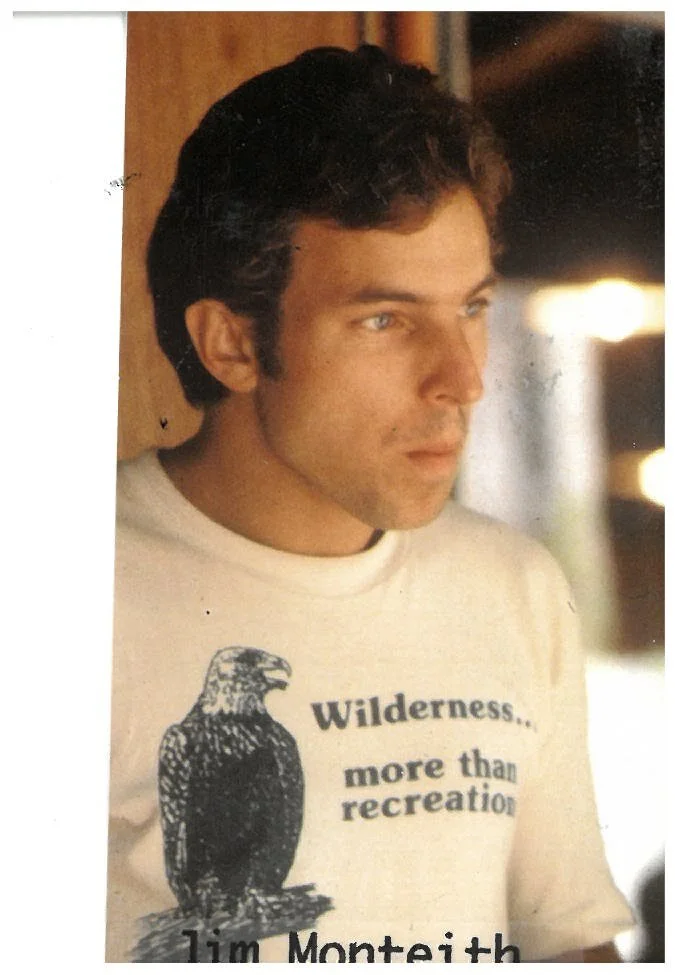

Figure 10. Monteith in his “Wilderness . . . more than [just] recreation” T-shirt, ca. 1980. A biologist at heart, he advocated a more biocentric and less anthropocentric wilderness ethic. Source: Oregon Wild.

2. Wild and scenic rivers are a mainstream conservation designation.

In 1968, Congress enacted the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA), naming eight wild and scenic rivers, including the lower Rogue in Oregon. The WSRA also designated twenty-seven additional free-flowing segments that had to be “studied” for wild and scenic river status, including the lower Illinois in Oregon. Until the mid-1980s, to save a stream as a wild and scenic river took not just one but two acts of Congress (first to study, then to designate). That all changed in 1988 with the enactment of the Oregon Omnibus Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which designated ~1,500 miles in more than forty free-flowing segments. Almost all had never been “studied” by the Forest Service or the BLM before being protected by Congress.

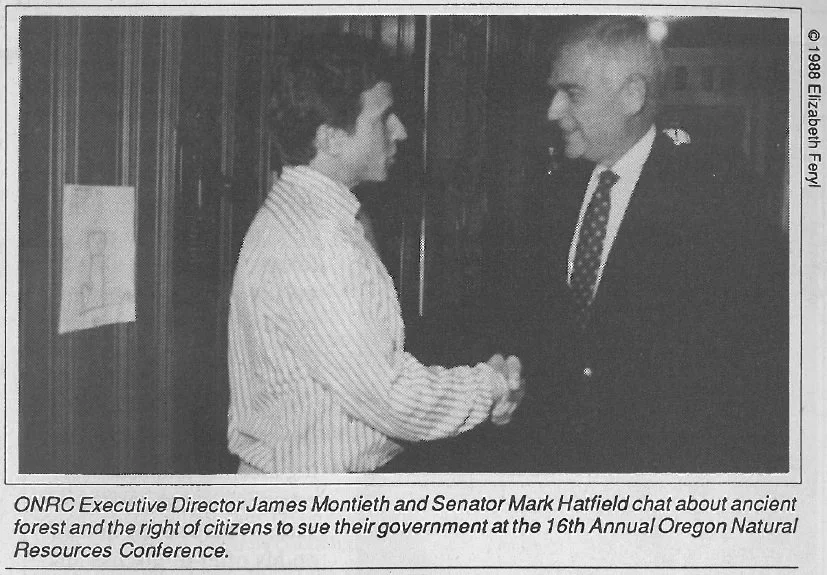

Senator Mark O. Hatfield became such a strong wild and scenic river advocate because

· he sought a political offset for his flagrant support of the liquidation of old-growth forests,

· he absolutely was not going to save the most threatened free-flowing stream in Oregon at the time (the upper Klamath River) from being damned,

· he absolutely was going to finish the infamous fish-killing and budget-busting Elk Creek Dam on a tributary to Oregon’s Rogue River, and

· river protection was wildly popular in Oregon. (That same year, Oregon voters would add the Klamath and several other Oregon streams to the Oregon Scenic Waterways System, the filing of which prompted Hatfield to do polling on the issue.)

Under the subsequent and more sincere leadership of Senator Ron Wyden, numerous free-flowing Oregon streams have been added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (with more in the pipeline)—including the Elk Creek Wild and Scenic River, which hosts a half-built dam with a huge notch in it so that Elk Creek again flows free.

3. Ancient forests of the Pacific Northwest are a national political issue.

We were trying to make old-growth forests a thing, and Monteith and I decided that “old growth” didn’t quite sing in a youth-worshiping society where “growth” as a noun is something a surgeon removes. We needed to up the brand. I wanted to call them “primeval” forests as in Longfellow’s opening line in “Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie” (“This is the forest primeval”). I had to admit that “primeval” was a rather archaic word that ignorant moderns might interpret as “prime evil.” Monteith won the debate by noting that “ancient” had but two syllables. With two weeks of our using the word while working the media, a headline with “ancient forest” appeared in the Eugene Register-Guard.

In 1989, the peak of old-growth-forest liquidation in Oregon, three square miles of such virgin forest were being clear-cut on federal public lands each week. At the time, Big Timber bought and sold (or least leased and rented) most Oregon elected officials. One could be for clean air and against litter, but the issue that separated the adults from the children in Oregon environmental politics was that of old-growth-forest logging (bumper sticker du jour: “Spotted Owls Taste a Lot Like Chicken” [actually, they taste more like bald eagle]).

These three themes continue and expand to this day.

Figure 11. Monteith chatting with Senator Mark Hatfield about “ancient forest.” While most of Oregon’s protected wilderness came at the sufferance of Hatfield, much de facto wilderness was lost due to the senator’s support of Big Timber. Source: Oregon Wild.

Monteith’s Biggest Obstacle

For the whole of Monteith’s tenure, by far the largest single obstacle to the conservation of Oregon’s forests was Oregon’s senior senator, Mark Hatfield. Until 1984, in addition to being the biggest obstacle to wilderness in Oregon, he was simultaneously the biggest opportunity. Wilderness bills for Oregon passed into law in 1972, 1978, and 1984, not coincidentally years when Hatfield sought and secured re-election.

After the Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 passed, Hatfield told me at 5:30 a.m. Central Time at Chicago O’Hare while we were waiting to board a flight to Washington DC that he would “never ever do another wilderness bill.” Having had to save real amounts of old-growth forests for the political expediency of his re-election that year was the end of the line for him. (Hatfield did do another wilderness bill [Opal Creek] in 1996, the year he did not seek re-election, but that’s another story.)

See Public Lands Blog posts: “Mark Odom Hatfield, Part 1: Oregon Forest Destroyer” and “Mark Odom Hatfield, Part 2: A Great but Complicated Oregonian”

There was no Oregon wilderness bill in 1990, the last time Hatfield sought re-election. In 1989, the courts halted old-growth-forest logging in northern spotted owl habitat. In 1990, the owl was listed under the Endangered Species Act. The clear-cutting of old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest had become a national political topic. The godfather of Oregon politics no longer controlled the issue. (It turns out the best way to fight a US senator is with other US senators.)

After that airport encounter in June 1984, it was clear to Monteith and me that another Oregon wilderness bill would not be enacted into law in 1990. Until that point, we had had an exponential graph in our heads based on those every-six-years wilderness bills since 1972 becoming ever larger in acreage and, most important, the amount of old-growth forest they protected. When the godfather of Oregon politics destroyed our hope, we had to go to Plan B: nationalize the issue of old-growth-forest logging.

A year or two later, Hatfield had a meeting with the editorial board of the Oregonian. It was common practice for a news reporter to attend and report any news. The timber reporter (not to be confused with the environment reporter that came later) called Monteith afterward to tell him that unprompted, Hatfield had launched a loud and sustained attack on the Oregon Natural Resources Council and most particularly Monteith and Kerr, claiming that we were radicals intent on destroying Oregon as we knew it. He had come across to the reporter as unhinged. Actually, if the Oregon as we knew it was clear-cutting three square miles of old-growth forest on federal lands each week, yes, we were out to destroy it.

A favorite saying of Monteith’s was “Our job is to make our opponents, and even our allies, more uncomfortable that we are.” Hatfield wasn’t the only member of the Oregon congressional delegation that Monteith made uncomfortable. At one point, I witnessed Representative Jim Weaver, who truly loved wilderness, grab Monteith by his lapels during a quite animated berating. Monteith’s fists, though down at his sides, were clenching and unclenching, but Monteith remained calm enough to avoid the charge of assaulting a federal official.

Another of Monteith’s favorite sayings was “We refuse to lose.” We did lose, but we viewed losses as temporary and were always seeking do-overs or to otherwise refine the outcome.

End of the Monteith Era at ONRC

Writing about James’s departure from ONRC in 1991, I said:

James Monteith played the leading role in transforming ONRC from a small but scrappy volunteer group to the largest independent volunteer group in the West and a nationally recognized leader on the ancient forest issue.

ONRC’s growth was due in large part to James’s willingness to take on the tough issues and fight hard. While many seemed willing ten years ago to duck the fight to save Oregon’s big old trees and free-flowing rivers, James knew that Oregon would not be Oregon without its ancient forests and wild and scenic rivers. At the same time, he realized to win these fights, Oregon conservationists would have to battle the big economic interests, sue the federal land agencies, and push the national conservation groups to lobby harder than ever . . .

James names Chief Joseph and Teddy Roosevelt as his two greatest inspirations to ever walk the Earth. These men are heroes for Monteith because of reverence for the land and their willingness to fight for it. In the same way, over the past two decades James Monteith has inspired countless conservationists with his passion for Oregon’s wild lands and his courage to protect Oregon’s natural heritage.

When I think back on the Oregon conservation era of James Monteith, the opening of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities comes to mind:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair . . .

During the time of James’s leadership, the wisdom, belief, light, and hope were ascendant. By the time Monteith left, ONRC had become an institution—though still a very scrappy and aggressive one.

Figure 12. James Monteith and noted American essayist, nature writer, and fiction writer Barry Lopez. Source: Oregon Wild.

Monteith’s Second and Third Acts

After he moved on from ONRC (now Oregon Wild), Monteith helped found Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and was the Oregon representative for Republicans for Environmental Protection. The former organization went on to thrive, while the latter went on to die. (It wasn’t James, it was the Republicans.)

Figure 13. Monteith rallying the troops at the Wallowa Lake Lodge near Joseph, Oregon. Source: David Mildrexler.

In his third act, among other things, Monteith helped found the Wallowa Land Trust and led an investor syndicate to save the historic Wallowa Lake Lodge. He is executive producer of Wallowology, which operates the Natural History Discovery Center in Joseph with the mission to “inform, inspire, and involve residents and visitors in the conservation of ecosystems and landscapes that support and sustain rural communities throughout Eastern Oregon.” Wallowology is a project of Eastern Oregon Legacy Lands.

James Monteith is not done.

Figure 14. James Monteith, Wallowology systems ecologist David Mildrexler, and Andy Kerr at a 2023 rewilding conference near Camp Sherman in the Metolius Basin, Oregon. Source: David Mildrexler (alas, neither he nor I recall who took the photo).

Thanks for everything, James.

Bottom Line: James Monteith not only moved the needle on Oregon public land conservation, he necessitated a new meter with a scale severalfold higher than the previous one.