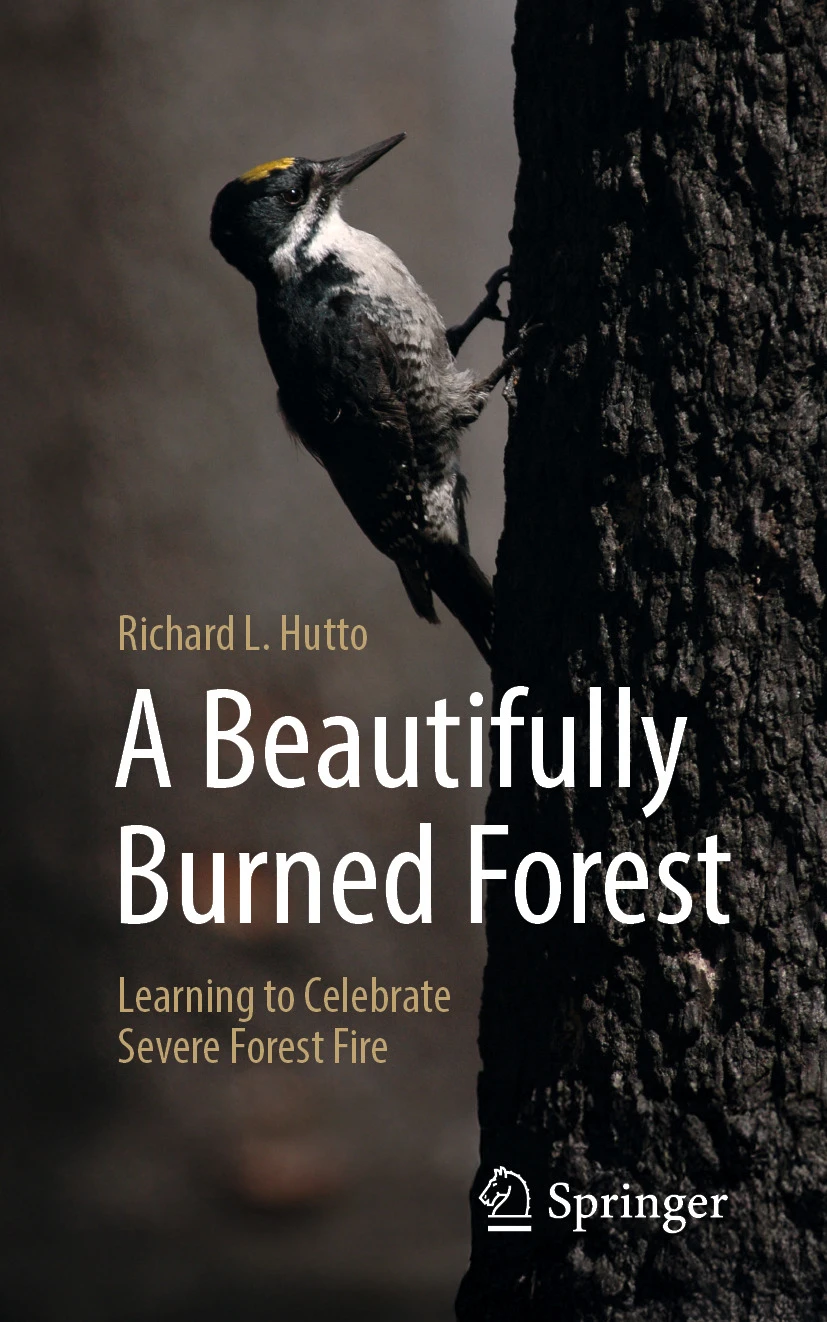

Book Review: “A Beautifully Burned Forest: Learning to Celebrate Severe Forest Fire”

Richard L. Hutto. 2025. A Beautifully Burned Forest: Learning to Celebrate Severe Forest Fire. Springer Books. $37.99 paperback, $19.24 Kindle.

Unfortunately, most people do not differentiate between wildland fire and structural fire even though, ecologically speaking, wildland fires are nearly always beautifully restorative events. Wildland fires ought to be viewed completely differently from the way we view fires that sometimes destroy whole communities. I have written this book to explain why it is so.

Richard Hutto

Figure 1. A freshly burned forest. Though it looks like hell to the mis-trained eye, it is nonetheless the necessary and inevitable beginning of the next forest. Just give it a bit of time, and neither salvage log nor replant it. Source: Wikipedia.

Richard Hutto is speaking truth to power (the fire-industrial complex) as well as to ignorance (most Americans) in his book about severe forest fire. The powerful include the federal land management agencies; Congress; federal, state, and local elected officials; Big Timber; and the private-sector fire-fighting industry. The ignorant include most of the media, indeed most of the American people, having drunk the Kool-Aid passed out by Smokey Bear. (As a youth, I did so imbibe, but the dose was not fatal.) The truth is that those severe forest fires that Smokey Bear warned us about are not bad, unnecessary, and preventable but are in fact good, necessary, and inevitable.

Figure 2. Glacier lilies, the vanguard of rebirth after the fires in Yellowstone National Park in 1988. Source: George Wuerthner.

Hutto is professor emeritus of biological sciences and wildlife biology at the University of Montana in Missoula. After the Yellowstone fires of 1988, he shifted his research focus to the ecology of birds in burned forests, and he hasn’t looked back.

Hutto is critical of the fire-industrial complex’s narrative that there are “good” and “bad” forest fires. “Good” if the fire burns at low intensity and consumes only brush and small trees but never big old trees. “Bad” if the fire burns with high intensity and results in the “loss” (to whom?) of big old trees. To Hutto (and to forest scientists and forests), a severe forest fire is a gift the forest receives; the forest is not destroyed by severe fire.

Figure 3. The 2013 Rim Fire, Stanislaus National Forest, California. A forest in full burn is a sight to behold from afar and scary as hell up close. Source: Wikipedia (Forest Service).

Among the powerful Hutto beautifully burns in his A Beautifully Burned Forest:

• fire “science” (“largely devoid of ecology”)

• The Nature Conservancy (“supposedly devoted to conservation”)

• Northern Arizona University emeritus professor Wally Covington, who has generalized his narrow findings about fire and forests near Flagstaff to apply to all forests from the Pacific Ocean to the Great Plains (“Nowhere is the extrapolation and lack-of-nuance problem more serious than when scientists like Covington claim that dry forest ecosystems of the entire West are in ‘widespread collapse’”)

• the fire-industrial complex, which “continues to sell the idea that we have a fire problem that can be addressed only through massive vegetation treatments and prescribed burning”

• Smokey Bear (“It seems that many of Smokey’s plant and animal friends find ideal conditions in the very burned forests we have been taught to hate!”)

Figure 4. Several years after the Yellowstone fires of 1988. Notice dead trees, both standing and fallen. Notice the profusion of fireweed. Notice that the young trees are thriving. Source: George Wuerthner.

Most people believe that wildfires harm salmon and trout. “Precisely the opposite is true,” writes Hutto. “Debris-laden flood events following severe fire are perfectly natural disturbance events that serve to stimulate stream channel reorganization, recruitment of large woody debris, pool development, and sediment recharge, which are real benefits to fisheries over the long haul.”

Then there is the presumed correctness of tree planting after a fire. Hutto accurately informs us that such is “almost certainly ecologically negative.”

Hutto argues that “we ought to value life associated with recently burned conditions as much as we value life associated with long unburned old-growth conditions.” In fact, scientists have found that a recently burned (but unlogged afterward) forest has even more biological diversity than an old-growth forest. That’s because a “pre-forest” created after severe fire has a legacy of large and small trees, both living or dead and standing or fallen, that is soon joined by a plethora of grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers. Extremely diverse habitats yield extremely high levels of biological diversity.

Figure 5. Townsend’s solitaire. This species has been found to nest in the upturned root wad of a tree felled by fire. Source: Wikipedia.

Figure 6. Mountain bluebird. Like several other species, this one soon finds severely burned forests. But it likes only those that have plenty of large dead trees, which means forests that didn’t have the life logged out of them before they burned. Source: Wikipedia.

Figure 7. The golden jewel beetle (Buprestis aurulenta), found from southern British Columbia through the Rocky Mountains to Mexico and in their greatest abundance in severely burned forests. Source: Wikipedia (Katja Schulz).

Burned forests harbor numerous plant and animal species (for example, morel mushroom, Bicknell’s geranium, jewel beetle, mountain bluebird, black-backed woodpecker, boreal toad) that are nowhere more abundant than in severely burned forests. Hutto notes that there are “more than 200 pyrophytic insect species whose presence and success on planet Earth depends on fire severe enough and large enough to initiate forest succession.”

Figure 8. Bicknell’s geranium, a species known to have waited two hundred years for that right severe fire to trigger its germination. Source: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Figure 9. Adult male black-backed woodpecker, with the characteristic yellow crown patch. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Figure 10. Adult female black-backed woodpecker. Source: Wikipedia.

To Hutto, “burned forests are magical places that seem to harbor plant and animal species and visual experiences found under no other forest condition.” So the next time one of your favorite forest areas severely burns, you need to do two things: (1) help stop the bureaucrats from logging the hell out of the area under the rubric of “salvage” and then planting one or two chosen species of trees, and (2) make aperiodic trips there for the rest of your life to witness and enjoy the rebirth of a forest. As it is fundamentally a human thing to do, it is okay to grieve the loss of the former forest and the awe it provided. Part of overcoming such grief is to allow yourself to be awed by the emergence of the next forest.

Figure 11. Boreal toad. Knots of these toads are known to move into burned forests in great numbers. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Figure 12. Williamson sapsucker (female on left, male on right). A cavity nester, this bird is rare in the first years following a fire but very common in later decades, when all those dead trees have developed all those nesting cavities.Source: National Park Service.

In re wildland fires, we humans need to embrace our inner pyrophilia, while at the same time redoubling our pyrophobia regarding structure fires. Government resources should be spent making structures safe from fires rather than continue to be wasted pretending to put out fires that should not be put out.

Buy the book. Read the book. Heed the book.

Figure 13. A 1940s poster titled “Smokey says—Burned timber builds no homes. Prevent forest fires.” Over the decades, the Forest Service has tweaked the message of Smokey Bear to appeal to modern sensibilities, but this is as close to the now-unstated truth as ever. Burned, er I mean unlogged, timber builds no homes. Source: US Forest Service, Smokey Bear Collection.