New Old Forests in New England, Part 2: Is the Vision Visionary Enough?

This is the second in a series of two Public Lands Blog posts on wildlands in New England. Part 1 examined the definitional, quantitative, and qualitative dimensions of these wildlands. Part 2 examines the impacts of Native Americans, the role of fire, and whether the vision for New England wildlands is ecologically and climatically adequate.

Figure 1. Old growth in a forest in New England, where old growth covers less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the land, according to Foster et al. 2023. Source: Harvard Forest.

To review: a capital-W Wildland is defined in Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future (Foster et al. 2023) as a tract “of any size and current condition, permanently protected from development, in which management is explicitly intended to allow natural processes to prevail with ‘free will’ and minimal human interference.” Part 1 of this series examined the extent and importance of these lands and emphasized that at some point, if untrammeled long enough, an old forest can again become an old-growth forest.

Here we turn to antecedents and prior influences on current Wildlands in New England, and evaluate visions for the future of these lands. Regarding what came before, Foster et al. (2023) write, “For many thousands of years, climate change and natural disturbances controlled the pace and nature of ecological change, with wildlife and human activity playing a subtle role in modifying ecological processes. Although a peopled land for millennia, New England was a vast, heavily forested, untrammeled region supporting an array of native plants and animals with concentrated areas of significant human impact.”

The Impact of Native Americans on New England Forests

“The concept of Wildlands embraces the enduring presence of Indigenous groups in New England,” say Foster et al. (2023). They explain that before European contact these peoples lived for millennia “in reciprocity with the whole land community, including old and majestic forests that allowed the full diversity of life to thrive.” Further, they point out that “Wildland conservation, like all of conservation, is only necessary due to unchecked development and destructive practices—first introduced to this region by colonizing people—that have threatened all natural systems and society itself.”

The fact is that Native Americans had little impact on the vast majority of forests in New England. There is scarce evidence that these peoples practiced horticulture, and pollen data indicate that forests were dense and mature for about eight thousand years before the onset of deforestation by Europeans (Oswald et al. 2020). Open lands developed only as a result of European agriculture. “Land managers seeking to emulate pre-contact conditions should de-emphasize human disturbance and focus on developing mature forests,” write Oswald et al.

Foster et al. (2023) explain that disturbances to the largely forested landscape before European contact were small-scale and infrequent, punctuated only by “infrequent, but occasionally intense, meteorological events, including hurricanes, windstorms, ice storms, and drought; outbreaks of insects and pathogens; and geographically constrained processes such as flooding and beaver activity.” Fire was uncommon, as detailed in the next section. Indigenous people lived in small, mobile groups that foraged and hunted for subsistence, and larger populations flourished where natural resources were abundant, in places like river valleys, large wetland systems, and along coastal marshes and estuaries. Thus, according to Foster et al., “the estimated one hundred thousand or so people exerted modest, though locally intensive impacts on the region’s 40 million acres of land.”

Figure 2. Binney Hill Wilderness Preserve before and after acquisition by the Northeast Wilderness Trust. The land was acquired in 2018, at which time the large log landing (top image) was heavily compacted and was habitat only for off-road vehicles. The installation of a gate and the spreading of native seeds resulted in a wildflower meadow full of bees and butterflies the following summer (bottom image). Already, native trees and shrubs are beginning to recolonize the former forest. The long-term goal is an old-growth forest. Hence, this is a capital-W Wildland. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

The Role of Fire in New England Forests

Nationally, fire is an important consideration in wildland conservation, but not so much in New England. The incidence of fire here has been low throughout much of the history of the region and is still low today. Oswald et al. (2020) report that “climate largely controlled fire severity in New England during the postglacial interval,” and Foster et al. (2023) corroborate: “Outside the cold and dry conditions that favored boreal species during the early post-glacial period, fire was uncommon on all but sandy outwash soils and rocky ridgetops.” Forest regeneration occurred not as a result of large burns but when one or several trees died and left small or moderate-size openings in the forest canopy, so long-lived and shade-tolerant tree species became prominent.

Today, this region is known nationally as the “asbestos forest” due to the fact that lightning fires are rare here. “An exception may be localized fire-prone landscapes such as glacial outwash plains, bedrock ridges, and mountain summits that support open and dry pitch pine and oak communities,” according to Foster et al. (2023). These authors note, however, that there was a great increase in fire following settlement and land clearing by the European colonists, especially during the nineteenth century. That was when “intensive logging, widespread clear-cutting, and regional farm abandonment created unusual conditions that allowed fires to flourish due to abundant fuels, ignition sources including locomotives, slash-and-burn fires, and carelessness, lax regulation, and limited control.” It is only because of this history that many landscapes in New England are considered fire-prone today.

Figure 3. The White River chock full of logs that were chock full of carbon around the turn of the twentieth century, when fires flourished in the region. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

In reality, from the mid-twentieth century until the present, there has been a dramatic decrease in fires thanks to “widespread recovery of maturing forests of low flammability, reduced ignitions, and increases in regulation, safety precautions, and control” (Foster et al. 2023). Most management guidelines now call for fires in the forests of New England to be controlled immediately, and sites managed with prescribed fire are excluded from consideration as Wildlands, explain Foster et al. (2023).

Figure 4. A species of scalycap mushroom that takes advantage of dead trees, demonstrating that there is more to an old-growth forest than just old trees. Source: Vermont Land Trust.

The Vision for Wildlands: Bold but Still Inadequate

The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the world. —Henry David Thoreau, Walking (first delivered at the Concord Lyceum, April 23, 1851)

Figure 5. Henry David Thoreau. Source: Wikipedia.

The Northeast of which I speak can be another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is that in New England, Wildlands can be the preservation of a significant portion of the world’s climate and nature—if the vision is bold enough.

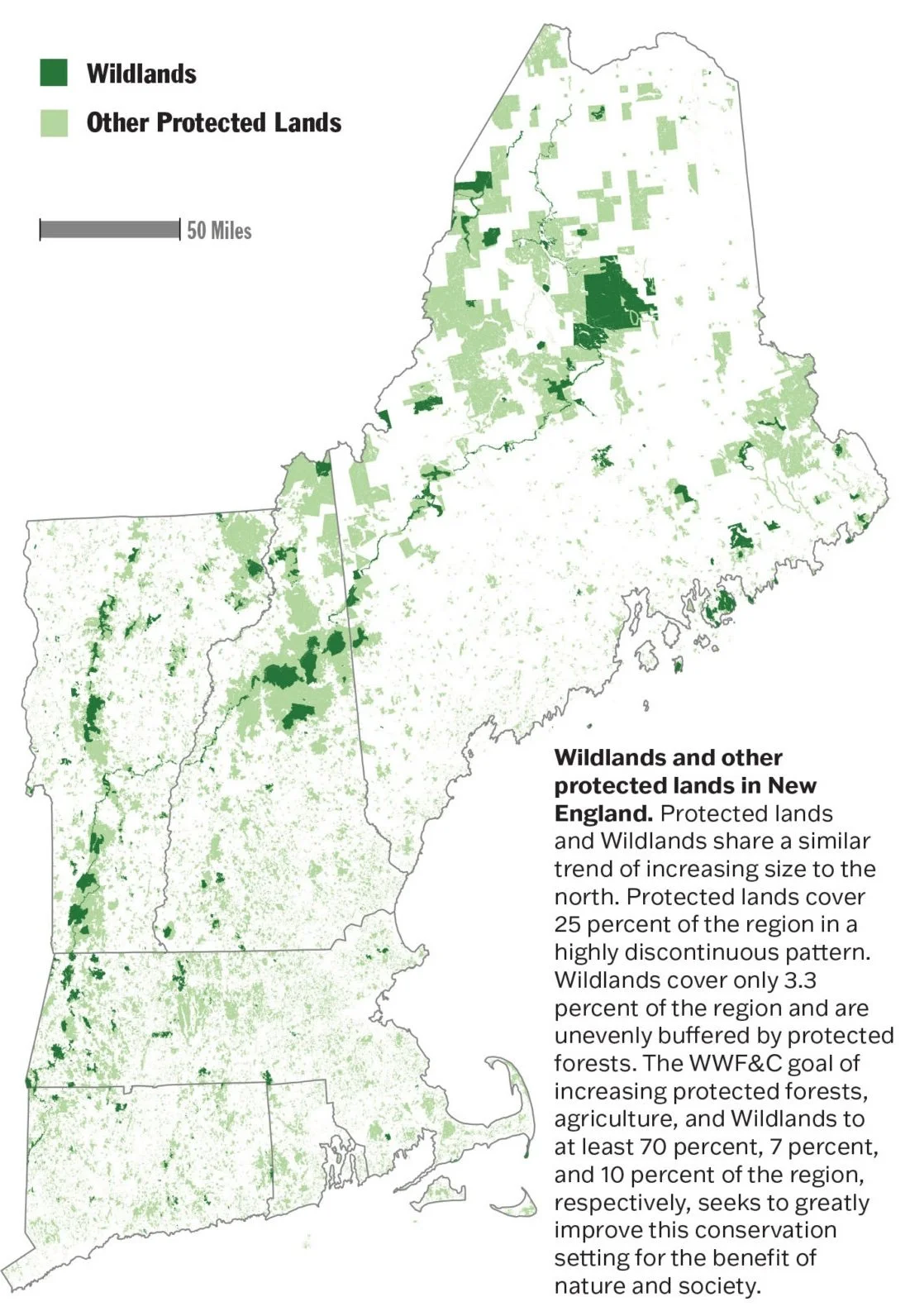

Wildlands of New England endorses a vision of New England proposed by Foster et al. 2017 that would “permanently protect by 2060 at least 70 percent of the New England landscape as forests, along with another 7 percent that is currently in agriculture—intact and in use for both nature and people.” Protected in this case means “permanently secured from development or conversion, with no specific reference to the type or intensity of management” (Foster et al. 2023). A protected forest, unless it is a Wildland, can be periodically logged off, over, and/or out. In this case, the more accurate term would be “protected timberland”—a timberland protected to produce timber. The vision is to designate at least 10 percent of these protected forests as Wildland reserves.

Figure 6. As defined in Wildlands in New England, Wildlands are a subset of protected lands, the vast majority of which cannot be developed further but can continue to be logged. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

Wildlands of New England promises to “evaluate increasing the goal for Wildlands in the region to as much as 20 percent of the land.” This is in light of the findings in that report, “the potential for New England to produce a greater proportion of the wood resources and food consumed in the region, and other national and international goals for Wildlands to address the crises of climate, biodiversity, and human well-being.” “As much as 20 percent” is not 30x30, let alone 50x50. To have functioning ecosystems with a full complement of native species across the landscape and over time, half of Earth needs to be dedicated to the conservation of nature (Dinerstein et al. 2017, Wilson 2016). While an inconvenient truth, protecting more Wildlands will mean less acreage in woodlands (areas that are logged) and less acreage in farmlands.

The vision needs to be bolder. Both despite and because of a population of 15.2 million humans, the potential is high to rewild the vast forestlands of New England. Most New Englanders live in incorporated areas, but fully half of Maine’s area is “unorganized territory” that has no local, incorporated municipal government, consisting of hundreds of townships primarily in heavily forested areas of the state with a grand total of only nine thousand residents. Vast amounts of private timberland can be converted to public forestlands and dedicated to the preservation and restoration of biological diversity, the conservation and restoration of watersheds, and the capture and storage of carbon. That is a vision bold enough to honor the words of Thoreau and the needs of our time.

Figure 7. Distribution of people and Wildlands in New England.The existing Wildlands are and future Wildlands will be in areas of very low to no population. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

References

Dinerstein, Eric, et al. June 2017. “An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm.” BioScience 67(6): 534–545.

Foster, David, et al. 2017. Wildlands and Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities: Broadening the Vision for New England (pdf). Harvard Forest, Harvard University.

———. 2023. Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future. Harvard Forest, Northeast Wilderness Trust, and Highstead Foundation.

Harvard Forest (website).

Oswald, W. Wyatt, et al. 2020. “Conservation Implications of Limited Native American Impacts in Pre-contact New England.” Nature Sustainability 3(3): 1–6.

Wilson, Edward O. 2016. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: Liveright.

Bottom Line: Bringing back old-growth forests at scale in New England can naturally remove massive amounts of carbon dioxide polluting the atmosphere, carbon that was once safely stored in big old trees.