New Old Forests in New England, Part 1: What, How Good, and How Much?

This is the first in a series of two Public Lands Blog posts on wildlands in New England. Part 1 examines the definitional, quantitative, and qualitative dimensions of these wildlands. Part 2 will examine the impacts of Native Americans, the role of fire, and whether the vision for New England wildlands is ecologically and climatically adequate.

Top Line: Both the need and the potential exist to allow vast acreages of New England forestlands to again become old-growth forests.

Figure 1. A recent path-making study of New England wildlands, telling us how much there is and how much the authors think there should/could be. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

“Old-growth forests comprise less than one-tenth of 1 percent of New England,” according to the authors of Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future (Foster et al. 2023). Before the European invasion, the vast majority of the landscape was forested and the vast majority of that was old-growth forests.

In the American West, public lands conservationists are mostly defending the pristine landscapes of roadless areas and/or mature and old-growth forests. They are fighting to preserve the last of an ecological legacy for future generations. In the American East, conservationists are mostly seeking to put sullied forests on a track to become old-growth forests again. They are fighting to restore a lost ecological legacy for future generations.

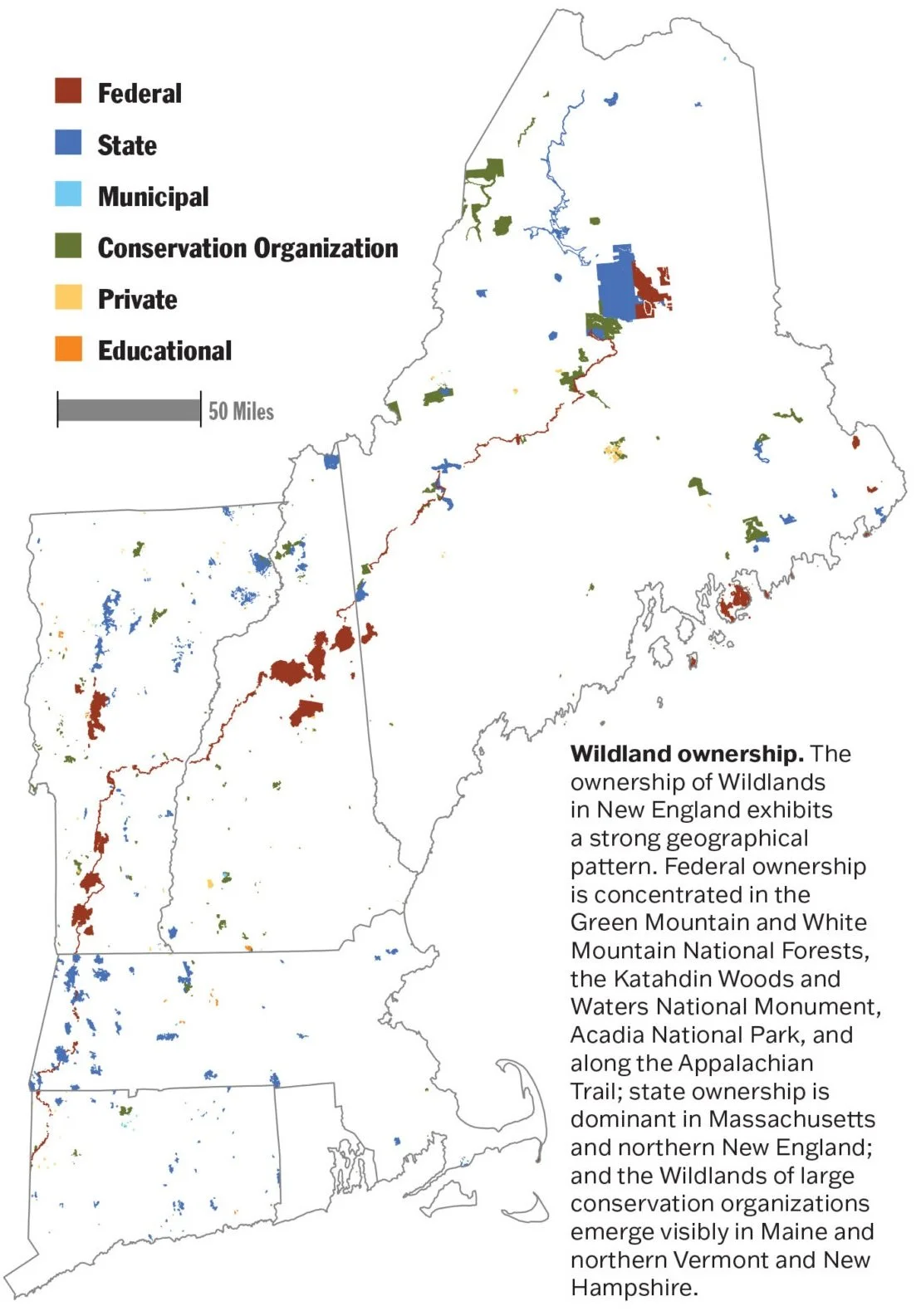

Figure 2. Unlike in the American West, in New England most wildlands are not federal public lands. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

“Wildlands”: West Is West and East Is East

As a westerner, I often use the term wildlands to mean protected wilderness, wilderness study areas, roadless areas, lands with wilderness characteristics (the latter two whether government-recognized or not), and the like. They are areas that are still generally natural, if not pristine.

Wildlands in New England (Foster et al. 2023) makes a distinction between wildland (not capitalized) and Wildland (capitalized). The book defines wildland and wilderness as terms “widely used in popular conversation” to mean “nature largely lacking in evidence of human impact.” This tracks with my Apple Dictionary: “tracts of land in a natural uncultivated state, typically regarded as having great environmental importance: we must protect the wildlands and their inhabitants for future generations.” This definition doesn’t depend on whether a tract is protected to remain in, or again become, a natural uncultivated state of great ecological importance.

By contrast, Wildlands in New England defines a capital-W Wildland as land where the intent, current and future management, and level of protection will allow it to remain (or become again) a wild land: “Wildland is free-willed, being allowed to develop without significant human intervention once designated, but may be in any current condition from past human use.” In other words, a Wildland in New England could be a freshly hammered landscape with roads and clear-cuts as long as it is on a legal and policy path to never be so hammered again.

Figure 3. Cedars on a bluff of shallow rocky soils above Lake Champlain that while not particularly large are at least two hundred years old. Rare plants also abound. Source: Vermont Land Trust.

While this capitalization convention works in written form, it wouldn’t work in conversation or in the audiobook or major motion picture versions of Wildlands in New England. In conversation, we need to be able to distinguish between the current state (natural or hammered) and future state (protected or vulnerable) of a lowercase-w wildland. In this Public Lands Blog post, I shall honor the capitalization convention of Wildlands in New England, but if we have to do more than write about it, we are reduced to saying “big-W wildlands” and “little-w wildlands.” I suggest we write of and speak to “protected” or “unprotected” wildlands that are currently “pristine” (never logged, mined, and/or plowed), “natural” (sufficiently recovered from being logged, mined, and/or plowed), or “recovering” (recently logged, mined, and/or plowed).

Wildlands in New England insists (as do I) that a Wildland isn’t such unless it is “untrammeled,” a word I ran across the first time I read the Wilderness Act of 1964:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. 16 USC 1131(c). [emphasis added]

My Apple Dictionary defines untrammeled as “not deprived of freedom of action or expression; not restricted or hampered: a mind untrammeled by convention.” Or a natural area untrammeled by humans. It’s worth noting the definition of the obverse, trammeled: “(usually trammels) literary a restriction or impediment to someone’s freedom of action: we will forge our own future, free from the trammels of materialism.” Or nature will forge her own future, free from the trammels of consumerism.

Before I looked it up, I presumed untrammeled meant the same thing as untrampled (trample: “tread on and crush” or “treat with contempt”). In this case, the latter word is a subset of the former.

Figure 4. Old black gum tree in the Vernon Black Gum Swamps in the Vernon (Vermont) Town Forest. Old-growth trees often have scaly bark and/or deep furrows like this one. Source: Vermont Land Trust.

Big-W Wildlands Further Defined

Wildlands in New England is quite specific about and insistent on its definition of Wildlands:

Our Wildland definition draws from conservation history; the federal Wilderness Act and its application; international standards for protected lands; and feedback from conservation scientists and practitioners.

Wildlands are tracts of any size and current condition, permanently protected from development, in which management is explicitly intended to allow natural processes to prevail with “free will” and minimal human interference. Humans have been part of nature for millennia and can coexist within and with Wildlands without intentionally altering their structure, composition, or function.

Three key criteria determine whether a property meets this definition:

Wildland intent. The property has a deliberate Wildland purpose.

Management for an untrammeled condition. The property is allowed to mature freely under prevailing environmental conditions and natural processes with minimal human intervention.

Permanent protection. Wildland intent and management are in perpetuity or are open-ended and expected to persist.

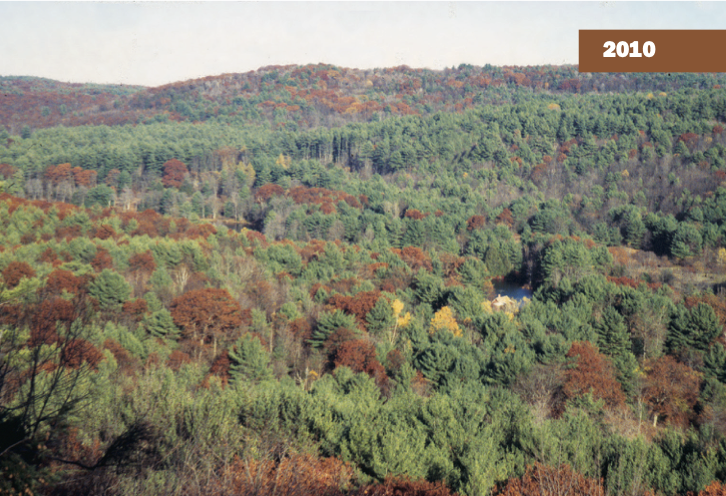

The wild condition of the land derives not from the land’s history but from its freedom to operate untrammeled, today and in the future. In New England, where the land has experienced widespread use, most Wildlands develop through a process of natural “rewilding” that is unconstrained by people and unpredictable in its dynamics. Although a few Wildlands may be true old-growth forests, others may be recently clear-cut areas or former pastures with legacies of human history. As Wildlands, all will develop old forest conditions over time. [emphasis in original]

Figure 5. Near the Swift River in Petersham, Massachusetts, in the 1880s. The old-growth forest was long gone and deforestation was peaking. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

Figure 6. The same spot near the Swift River in Petersham, Massachusetts, in 2010. Leave it alone and give it enough time, and it will again be an old-growth forest. Source: Foster et al. 2023.

Why Wildlands?

Wildlands in New England reminds us of the importance of wildlands/Wildlands:

[T]here are myriad reasons to protect Wildlands:

• Most importantly, Wildlands hold immense intrinsic value—wild nature simply has a right to exist, as do all of the species that inhabit Wildlands.

• Wildlands are essential for maintaining and increasing biodiversity. Over time, Wildlands that are allowed to mature under the influence of natural processes will support unique ecosystems, rich assemblages of species, and many structural features missing from much of the actively managed landscape.

• Wildlands are critical in mitigating climate change by storing vast quantities of carbon.

• Wildlands add key contributions to a resilient landscape, with their complexity and diversity.

• Wildlands offer quiet space for spiritual and physical renewal.

• Wildlands can serve as ecological references for scientific inquiry as well as forest management and conservation.

• Finally, Wildlands form a central component of 30x30, the national and international goal to protect 30 percent of the land and waters of the Earth to address the looming crises of biodiversity, climate change, and human welfare.

Figure 7. A presettlement forest ca. 1700 as represented in a diorama at Harvard Forest’s Fisher Museum. Virgin old growth is so rare in New England that one is often reduced to viewing it in a museum. Source: Harvard Forest Fisher Museum.

New England Wildlands by the Numbers

New England (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) has 40.2 million acres of land (in comparison, for me at least, Oregon is half again as large), of which 81 percent is forested. Protected Wildlands, which are almost all forested, total 1.3 million acres, or 3.3 percent of New England.

Protected Wildlands comprise 426 individual units of federal, state, municipal, nongovernmental, educational, and privately owned land, ranging in size from less than 10 acres to more than 150,000 acres. (An acre is the area between 5-yard lines on an American football field.)

Figure 8. A Fisher Museum diorama of an old-growth forest on the shore of Harvard Pond. The site was too rocky for agriculture. Source: Harvard Forest Fisher Museum.

Real Versus Re-emerging Old Growth

Wildlands in New England also offers separate definitions for old-growth forest and old forest

old-growth forest

Forests with abundant old trees and structural features, including snags, downed trees, and pit and mound topography, that exhibit minimal evidence of human land use. Old-growth forests comprise less than one-tenth of 1 percent of New England.

old forest

Forests with some of the structural characteristics of old-growth forest, including old trees, but which may have had significant human influence in the past and may be actively managed.

Because old-growth forests are so rare there, the definition in Wildlands in New England goes beyond the usual description of a condition to include a statement on the extent of the condition.

In old (the original) England, the term they use for an old-growth forest is ancient woodland. In the United Kingdom, an ancient woodland is a forest that has existed continuously since 1600 (or 1750 in Scotland). According to Wikipedia, “planting woodland was uncommon before those dates, so a wood present in 1600 [1750] is likely to have developed naturally.” But given the technological ability of the human inhabitants, such forests still could have been logged before 1600.

At some point, if untrammeled long enough, an old forest can again become an old-growth forest.

Figure 9. Another Fisher Museum diorama, this one with a couple of human figures for scale. Source: Harvard Forest Fisher Museum.

In Part 2, we shall examine the impact of Native Americans on New England forests before New England became a thing, the impacts (or lack thereof) of fire on such forests, and whether the Wildlands vision for New England forests is visionary enough.

For More Information

Asselin, Ray. 2018. The Lost Forests of New England: Eastern Old Growth (video). New England Forests YouTube channel.

———. 2020. Eastern White Pine: The Tree Rooted in American History (video). New England Forests YouTube channel.

———. 2024. The Return of Old Growth Forests (video). New England Forests YouTube channel.

———. 2025. Old Growth Forests—Nature’s Biotic Water Pump (video). New England Forests YouTube channel.

D’amato, Anthony, and Paul Catanzaro. Undated (~2022). Restoring Old-Growth Characteristics to New England’s and New York’s Forests (pdf). University of Vermont and University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Dinerstein, Eric, et al. June 2017. “An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm.” BioScience 67(6): 534–545.

Fisher Museum. The Harvard Forest Dioramas. Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts.

Foster, David, et al. 2017. Wildlands and Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities: Broadening the Vision for New England (pdf). Harvard Forest, Harvard University.

———. 2023. Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future. Harvard Forest, Northeast Wilderness Trust, and Highstead Foundation.

Harvard Forest Harvard Forest, Highstead Foundation, and Northeast Wilderness Trust. Wildlands in New England: Interactive Web Map.

Highstead Foundation (website).

Langlois, Krista. June 10, 2024. “The Northeast Has Unexpected Old-Growth Forests That Survived Colonial Axes.” Sierra magazine.

Leverett, Robert T. August 25, 2018. “Eastern Old-Growth Forests Then and Now.” Rewilding Institute.

Maloof, Joan. 2011. Among the Ancients: Adventures in the Eastern Old-Growth Forests. Washington, DC: Ruka Press.

New England Wildlands 2023 (map, pdf). From Foster, David, et al. 2023. Wildlands in New England: Past, Present, and Future.

Northeast Wilderness Trust (website).

Old-Growth Forest Network (website).

Public Lands Blog posts:

“Forests in the American East, Part 1: A Pandemic of Shifting Baseline Syndrome.” March 20, 2023.

“Forests in the American East, Part 2: A Plague of Early Successional Habitat.” April 1, 2023.

“Forests in the American East, Part 3: A Vision of the Return of Old-Growth Forests.” April 21, 2023.

“National Forests in the Eastern United States: An Incomplete Legacy.” January 7, 2017.

“Welcoming Back Pumas to the Eastern United States.” March 13, 2024.