Top Line: The Forest Service is blowing President Biden’s chance of saving mature and old-growth forest for this and future generations.

Figure 1. Cover photo, and the only photo, in the Forest Service’s National Old-Growth Amendment Draft Environmental Impact Statement. If there ever were stands of old-growth forest that don’t need any kind of “restoration” management, it’s those in the temperate rainforest of the Oregon Coast Range, in this case the Siuslaw National Forest. Source: USDA Forest Service.

In 2022, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that required the US Forest Service (USFS) to, among other things, “develop . . . conservation strategies that address threats to mature and old-growth forests on Federal lands.” The USFS has responded by issuing a draft National Old-Growth Amendment (NOGA) that would amend nearly all national forest land management plans. The NOGA has enough loopholes to drive lots of log trucks through. Public comments are urgently needed by midnight Pacific Time on September 19, 2024, to influence the Biden administration to overrule the USFS in this matter.

NOGA Background

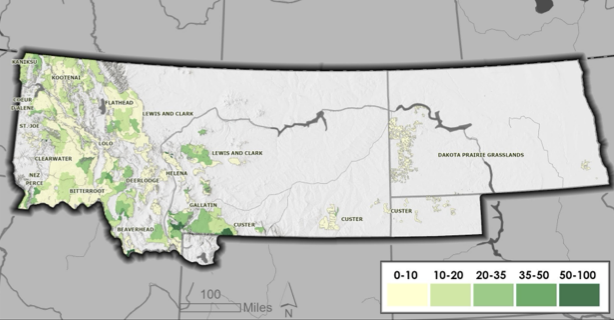

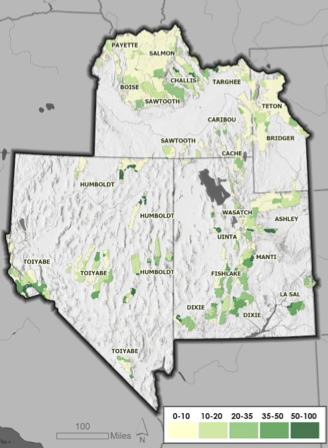

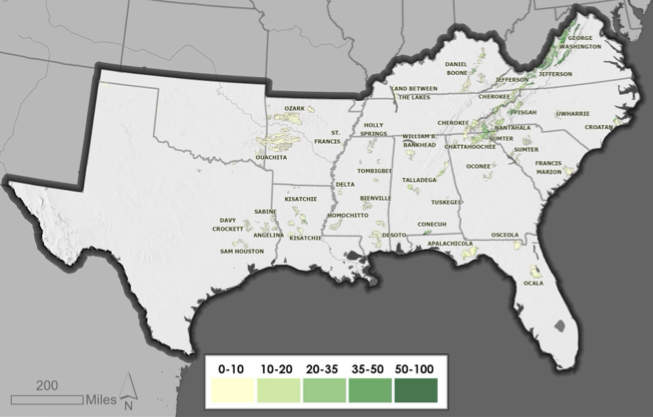

Before issuing the NOGA, the USFS (and the Bureau of Land Management) prepared an inventory of mature and old-growth (MOG) forests. (See my Public Lands Blog post “How Much Mature and Old-Growth Forest Does the US Have Left?”) A deficiency of the MOG inventory is that while it can tell us how much mature and old-growth forest remains on federal public lands, it can only tell us where the MOG forests are at the coarsest of scales (Figure 2). (At this end of this Public Lands Blog post are regional maps of where generally the mature and old-growth forests are in the National Forest System.)

Figure 2. Where old growth is found in the National Forest System. Source: US Forest Service.

After they published their inventory, the USFS and the BLM issued an “Analysis of Threats” to MOG forests, which found that logging by the agencies is not a significant threat. Rather, MOG forests are threatened mostly by too much fire, not enough fire, insects and disease, extreme weather events, and/or climate change. Contrary to reality, the agencies don’t view themselves as a threat to mature and old-growth forests but rather as the saviors of old-growth forests. With a straight face, the USFS notes that “the lack of large log milling may hinder restoration and other vegetation management activities to improve ecological conditions in or near old-growth forests.”

In the NOGA, the USFS generally contends that judicious logging of old growth can save said old growth. Readers in my age cohort might remember those who argued during the Vietnam War that villages needed to be bombed to save said villages.

Figure 3. Old-growth forest on the Fremont-Winema National Forest in Oregon. Source: US Forest Service.

What the NOGA Would Do

Not much, really. Each national forest plan would be amended by the inclusion of nationally mandated language that sets a goal; prescribes management approaches; lists desired conditions, objectives, standards, and guidelines; outlines plan monitoring requirements; and includes a “statement of distinctive roles and contributions” for old-growth forests.

The NOGA considers a no-action alternative and three action alternatives that are identical save for the “standards” they include. Of course, the draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) is written to justify the preferred alternative, Alt 2, which includes the full suite of standards. Alt 3 would expand one of the standards to say: “Proactive stewardship in old-growth forests shall not result in commercial timber harvest.” (This is why EIS’s should be written by the Environmental Protection Agency or another federal agency that doesn’t have the biases any action agency does.)

If you wade through all the proposed verbiage (I did, but I’m not afraid of anything I can wash off or throw up), you will come away disappointed. In essence, the USFS is saying in the NOGA

• it cares about old growth,

• it will give more lip service to old growth, but

• the only way to save old growth from all those threats is to manage (the USFS likes the term steward, which means log in this case) old growth.

Better Than Nothing, or Nothing Is Better?

A happy take on the USFS NOGA is that the agency is recognizing for the first time the importance of old-growth forests, and such is, well, a start. A pessimistic (pronounced “realistic”) take is that no NOGA is better than this NOGA. Unless the USFS drastically changes its proposed action in the NOGA, the best thing for MOG on the national forests is for the final NOGA never to see the light of day.

If there is a stand of old-growth forest that has stood for a millennium, there is nothing in the USFS’s proposed new management direction that forbids the agency from logging it (of course, in the name of saving it). There is no age of old-growth forest that is too old for the Forest Service to “save.”

If the Forest Service definition of old growth for a particular forest type is a minimum of eight large trees per acre, then an acre that includes twelve such large trees can be shorn of four of those large trees and still be classified as old growth. If an acre has only seven large trees, then screw it, according to the Forest Service.

Figure 4. Cover photo, and the only photo, in the Forest Service’s “Technical Guidance for Standardized Silvicultural Prescriptions for Managing Old-Growth Forests.” If there ever were stands of old-growth forest that don’t need any kind of “restoration” management, it’s those in the temperate rainforest of the Oregon Coast Range, in this case the Siuslaw National Forest. Source: USDA Forest Service.

Why the Forest Service Is Such a Disservice

The Forest Service, an agency of the US Department of Agriculture, historically treated any forests of commercial value as a row crop: harvest, plant, harvest, plant, harvest . . . I guess it’s progress that the agency now views forests as more like an orchard, which cannot be sustained without a lot of management.

Like all bureaucracies, the USFS is made up of bureaucrats. If there is one thing all bureaucrats hate, it is to have their discretion limited. Truly saving old-growth forests and trees for this and future generations means limiting the discretion of USFS bureaucrats to manage or choose between competing uses (where many actually are abuses).

The Biden executive order addressed both “mature” and “old-growth” forests and trees equally. Conservation strategies were to address the threats to both. However, the USFS has failed to address mature forests in the NOGA, other than to note that some mature forests might later be drafted to become old growth. In essence, the agency choked on the M in MOG when it discovered how much M forest exists. Saving mature forests would mean the agency’s logging sandbox would be substantially diminished. The USFS is also banking on the public placing less value on mature as compared to old-growth forests.

As far as the NOGA goes, to the USFS old growth is never a place nor an ecosystem but merely a silvicultural state. If a fire converts an old-growth forest to a preforest (aka early seral forest, quite the ecosystem in itself), the “protections of the NOGA” no longer apply. The USFS will likely want to salvage log the old dead trees and quickly plant new ones so the site can, over silvicultural time, become “old growth” again. (See my Public Lands Blog posts: “Preforests in the American West, Part 1: Understanding Forest Succession.” and “Preforests in the American West, Part 2: “Reforestation,” By Gawd?”.)

Concurrent with the NOGA, the Forest Service is updating Forest Service Manual 2470: Silvicultural Practices. Silviculture is the “growing and cultivation of trees.” This NOGA is the product of a silvicultural circle jerk. (Lest you are aware only of the definition of this term offered second in my Apple Dictionary, permit me to offer up the first definition:

1 informal a situation in which a group of people engage in self-indulgent or self-gratifying behavior, especially by reinforcing each other’s views or attitudes: “those award ceremonies are big circle jerks.”

Figure 5. Old-growth forest on the Bitterroot National Forest in Montana. Source: US Forest Service.

The USFS view is generally that old growth cannot be left to nature but must be actively stewarded by foresters. While this is depressing, don’t be depressed. The Biden administration can save the old-growth forests from the Forest Service. Part of Joe Biden’s legacy can be actually saving the old-growth forests for this and future generations.

How You Can Help

For the conservation community to make the case for the Biden administration to act decisively and overrule the Forest Service before the new president takes office on January 20, hundreds of thousands of comments must be submitted on the NOGA. That’s where you come in. The USFS (actually the White House) needs to hear from you!

You can send an official comment to the USFS through the Climate Forests Campaign (CFC) action webpage. After you submit your comment through that portal, the CFC will bundle it with others’ comments and submit the lot through the official USFS web portal. (The CFC will also be making sure the White House knows of your and all that other public support to really protect old-growth forests.)

It is vital that you send your comment for the official record by midnight Pacific Time on September 19, 2024.

The CFC offers suggested language for your comment. Please delete the language in the comment box and then copy and paste the following language (much of which is the same, but with some important additions):

The Forest Service should adopt a record of decision that is a strengthened version of Alternative 3 in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement—modified as recommended in detailed joint comments you are receiving from a coalition of national, regional, and local conservation and public interest organizations.

Mature and old-growth trees and forests protect our climate by absorbing and storing carbon, boost resilience to fire, help regulate temperatures, filter drinking water and shelter wildlife. Logging them deprives us of the benefits and beauty of our largest, oldest trees.

The proposal allows old-growth trees to be sent to the mill and allows agency staff to manage old-growth out of existence in pursuit of “proactive stewardship” goals. The draft also contains ambiguous language that could be used to justify continued commercial logging of old growth in the Tongass.

The final record of decision should:

1. End the cutting of old-growth trees in all national forests and forest types and end the cutting of any trees in old-growth stands in moist forest types.

2. End any commercial exchange of old-growth trees. Even in the rare circumstances where an old-growth tree is cut (e.g. public safety), that tree should not be sent to the mill.

Cutting down old-growth trees to save them from potential threats is a false solution. They are worth more standing.

Mature forests and trees–future old growth–must be protected from the threat of commercial logging in order to recover old growth that has been lost to past mismanagement. They must be protected to aid in the fight against worsening climate change and biodiversity loss. And they must be protected to ensure that our children are able to experience and enjoy old growth.

Failure to protect our oldest trees and forests undermines the objectives of this amendment, contravenes the direction of EO 14072, and ignores 500,000+ public comments the agency previously received.

The vague language at the end of the first paragraph is because the referenced comments have yet to be finalized and sent. Rest assured they are going in, and they will be good. (I’m helping to draft them.)

Don’t delay. Please act now before you forget or get distracted. Here’s the link again.

Figure 6. A tiny sequoia in front of a giant sequoia on a national forest in the Sierra Nevada of California. Source: US Forest Service.

Bottom Line: Send your comment now! It won’t persuade the Forest Service, but it could help persuade the White House.

Figure 7. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Northern Region (Region 1). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 8. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Rocky Mountain Region (Region 2). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 9. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Southwestern Region (Region 3). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 10. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Intermountain Region (Region 4). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 11. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Pacific Southwest Region (Region 5). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 12. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Pacific Northwest Region (Region 6). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 13. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Southern Region (Region 8). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 14. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Eastern Region (Region 9). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 15. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Alaska Region (Region 10). Source: US Forest Service.