This is the second of a two-post exploration of the stage of forest succession that occurs after a stand-replacing event and before the canopy again closes and dominates the site. Part 1 discussed why preforests are valuable, if undervalued. Part 2 addresses management of preforests to preserve their ecological value.

Figure 1. Mountain (shown here) and western bluebirds strongly prefer preforests. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

If net present value of timber production is your goal, you want the preforest stage to be as short as inhumanely possible. Whether the trees were killed by clear-cutting or nature, by all means send as much of the forest to the mill as possible. Then densely plant a monoculture of Douglas-fir (or ponderosa pine, depending upon where you are) seedlings and spray the plantation with herbicides and/or hand-slash so any broadleaf vegetation doesn’t compete with the new conifer seedlings. Since time is money and forty years is the most profitable rotation age for production forestry, you cannot be wasting any of those years on the preforest stage.

The traditional response of the Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and private industry after a stand-replacing event has been to immediately salvage log it (akin to mugging a burn victim) and then densely plant it with a monoculture of one species, usually Douglas-fir. The intent has been to short-circuit this stage of natural forest succession and reestablish the young forest stage. Of course, ecologically the plantation is more akin to a cornfield than a forest, but it has been “reforested,” by gawd.

Fortunately, the times are a-changin’ as understanding of preforests improves.

Complex Versus Simplistic Early Successional Forest Ecosystems

Not all preforests are created equal.

If the disturbance was natural—wildfire, wind, insect, avalanche, or volcano—the preforest stage is rich in the legacy of trees (living or dead, standing or fallen) that continue to influence the structure and function of the ecosystem. This is a complex preforest.

If salvage logging followed a natural disturbance or if the stand was clear-cut—perhaps accompanied by one or more doses of prejudicial herbicides and then a precommercial thinning to remove the excess conifers that were established due to the herbicides—it is a simplistic preforest.

The Douglas-fir region abounds in simplistic preforest but is rather short on complex preforest. Simplistic preforest on private timberlands has some—but not a lot—of habitat value. Certain species and ecological processes just won’t be found in simplistic preforest. However, as there is a lot of simplistic preforest, there is significant total value on a whole-landscape basis.

Figure 2. The poster plant for complex preforests is Vaccinium membranaceum (that’s mountain huckleberry, mountain bilberry, black huckleberry, tall huckleberry, big huckleberry, thin-leaved huckleberry, globe huckleberry, or Montana huckleberry to you). Source: Wikipedia.

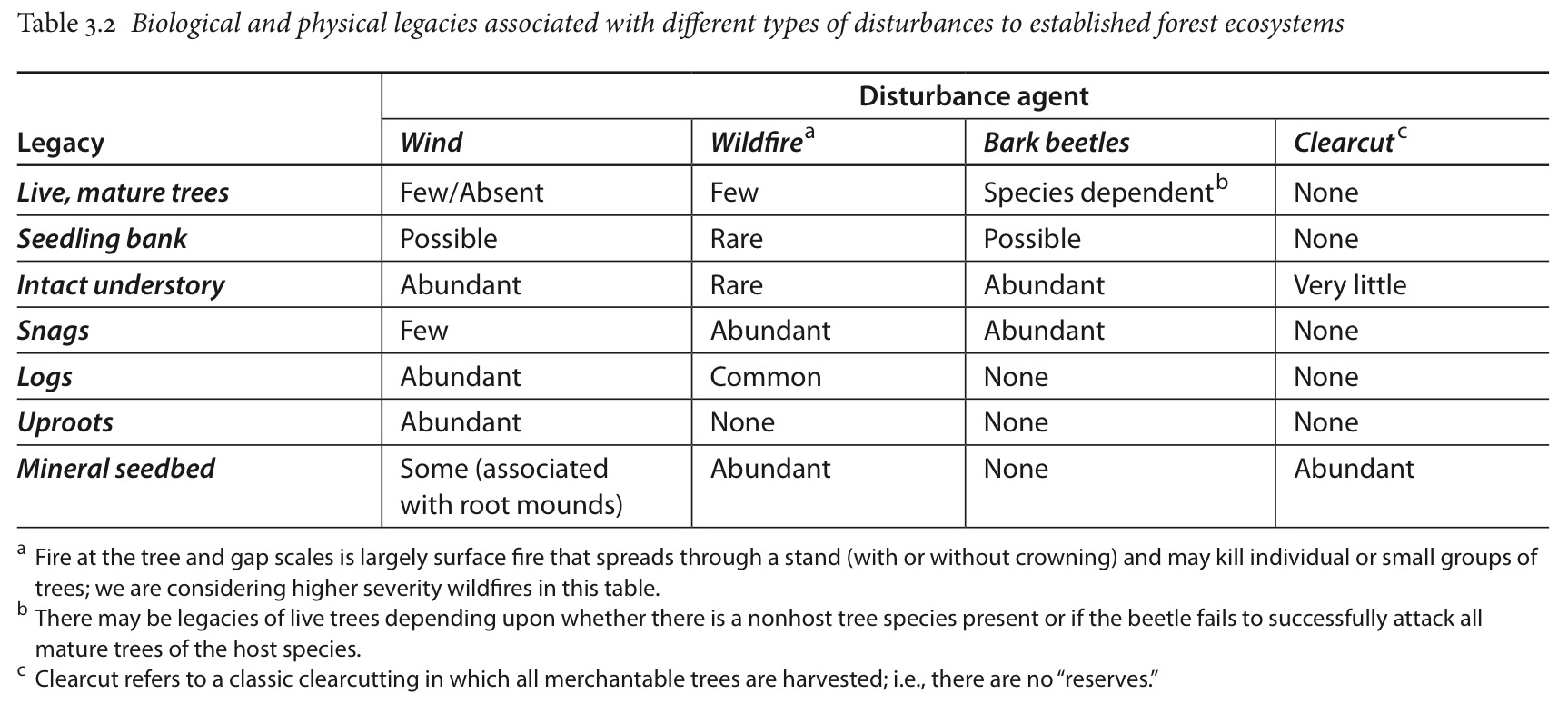

Depending upon the cause of the stand-replacing event, combinations of various biological legacies, including live standing trees, dead standing trees (snags), and fallen trees (large woody material), can be found in the preforest stage (Table 1). Some events leave the understory undisturbed, while others do not. In the American West, besides the legacy of large wood (living and dead, both standing and fallen), preforests often host hardwood trees as well as conifers, along with herbs (pronounced “wildflowers”), shrubs, and graminoids (“sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses are hollow”).

Table 1. Biological legacies by disturbance agent. Additional disturbance agents include volcanic eruptions, snow avalanches, and severe floods. Source: Ecological Forest Management.

Bring Back the Black-Backeds

In “The Forgotten Stage of Forest Succession: Early-Successional Ecosystems on Forest Sites,” Swanson et al. report:

Naturally occurring early-seral pre-forest communities appear to constitute a unique system on the seral spectrum for forested lands of the [Pacific Northwest]. The structural attributes offered by this set of conditions provide habitat for a number of conservation-dependent species, as well as many species that are not rare, but are of substantial social and economic value (i.e., game animals such as deer, elk, and bear).

Furthermore:

Our research, while exploratory in nature, suggests that complex early-seral communities have importance on par with complex late-seral forests in providing habitat for conservation-listed species. . . . While not final due to the evolving state of knowledge on early-seral communities and the habitat dependencies of many wildlife species, the conclusions presented here suggest that early-seral conditions play an important role in maintaining a number of societally important values, including rare or conservation-dependent species.

As the northern spotted owl is to old-growth forests, so the black-backed woodpecker is to preforests. The bird’s back is black so it doesn’t stand out when dining on insects found under the scorched bark. As the Center for Biological Diversity notes:

An intensely burned forest of dense, fire-killed trees is perhaps the most maligned, misunderstood and imperiled habitat. Far from being destroyed, a naturally burned forest harbors extraordinarily rich biological diversity, and there’s no better flagship species to help us embrace that than the black-backed woodpecker. . . .

[T]he woodpecker prefers its mature and old-growth trees to be snags—because it loves to eat the wood-boring beetles that flock to large dead and moribund trees, responding to insect outbreaks following fires, windfall, and large-scale drought- or beetle-induced mortality events.

Black-backed woodpeckers depend upon an unpredictable and ephemeral environment that may remain suitable for at most seven to 10 years after fire; their populations are clearly regulated by the extent of fires and insect outbreaks—and by the management actions people choose to take in those affected forests.

Figure 3. The black-backed woodpecker is the spotted owl of the preforest. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Salvage logging is deadly to Picoides arcticus. Complex preforest is also the required or preferred home of many other wildlife species, including several that are “species of concern” due to trends of population decline, including bluebirds (western and mountain). Butterflies and moths of all kinds as well as deer and elk thrive in complex preforest.

The Good News, the Bad News, and My Recommendations

The good news is that the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management are doing far less salvage logging after stand-replacing events. Public opposition, a lack of industry capacity to absorb the large pulse of logs, and other bureaucratic factors have combined so that the amount of complex preforest on federal public lands is on the increase (a rare bit of good news).

The bad news is that some federal forest managers, while not salvage logging after a stand-replacement event, are nonetheless planting nursery seedlings in a misguided attempt to be (seen to be) doing something after a wildfire.

My recommendations to address concerns about preserving the ecological value of preforests follow.

On private lands: (1) State laws that require the prompt planting of conifers after clear-cutting on private lands should be repealed. While industrial private timberland owners will continue to so plant, there are nonindustrial owners who desire to apply the principles of ecological forestry, which honor the preforest stage. (2) For a variety of reasons—public health, ecological health, and watershed health—herbicide application on preforests should be banned.

On public lands: Salvage logging should never occur after a stand-replacing event (and neither should planting nursery seedlings).

On all lands: The Forest Service, as part of its Forest Inventory and Assessment Program, should inventory and assess the extent and quality of preforest across all ownerships and site classes. One cannot value or manage what one does not count.

Figure 4. The three-toed woodpecker is another aficionado of preforests. Source: Flckr.

Back to Opal Creek

Senator Mark Hatfield, who did more than anyone to facilitate the logging old-growth forests (and rapidly replanting monocultures) (see Public Lands Blog posts Mark Odom Hatfield Parts 1 and 2), nonetheless—or perhaps because of—did the right thing for Opal Creek. In one of his last acts as a US senator, the statute creating the Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area, is this clause (included, dare I brag, by my incessant whining to Hatfield staff):

(ii) SALVAGE SALES.—The Secretary [of Agriculture {Forest Service}] may not allow a salvage sale in the Scenic Recreation Area.

Bottom Line: When I return to the Opal Creek Wilderness within the Opal Creek Scenic Recreation , I will enter bittersweet and leave happy—happy in knowing that the forest continues its natural succession.

For More Information

DellaSala et al. “Complex Early Seral Forests of the Sierra Nevada: What Are They and How Can They Be Managed for Ecological Integrity?” Natural Areas Journal 34 (July 2014):310-324.

Franklin et al. Ecological Characteristics of Old-Growth Douglas-fir Forests. USDA Forest Service, PNW Research Station, 1981.

Franklin et al. Ecological Forest Management. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2018.

Oliver, C. D, and B. C. Larson. Forest Stand Dynamics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990.

Smith et al. “Peak Plant Diversity During Early Forest Development in the Western United States.” Forest Ecology and Management 475 (November 2020):118410.

Swanson et al. “The Forgotten Stage of Forest Succession: Early-Successional Ecosystems on Forest Sites.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (March 2011, first published online March 2010):117–125.

Swanson et al. “Biological associates of early-seral pre-forest in the Pacific Northwest.” Forest Ecology and Management Volume 324 (15 July 2014): 160-171

Ulappa et al. “Silvicultural Herbicides and Forest Succession Influence Understory Vegetation and Nutritional Ecology of Black-Tailed Deer in Managed Forests.” Forest Ecology and Management 470–471 (August 2020):118216.