In 1945, a bill was introduced in Congress “to provide a system of foot trails to complement the nation’s highway system.” It never got a hearing. In 1965, in a message to Congress, President Lyndon Johnson said, “We can and should have an abundance of trails for walking, cycling, and horseback riding, in and close to our cities. In the backcountry we need to copy the great Appalachian Trail in all parts of America.” In 1968, Congress enacted the National Trails System Act, which has been amended numerous times to add more trails. As the National Trails System turns fifty, we reflect on its extent and intent, on the contribution it makes (or does not make) to public lands conservation, and on pending legislation to extend or elevate trails in the system.

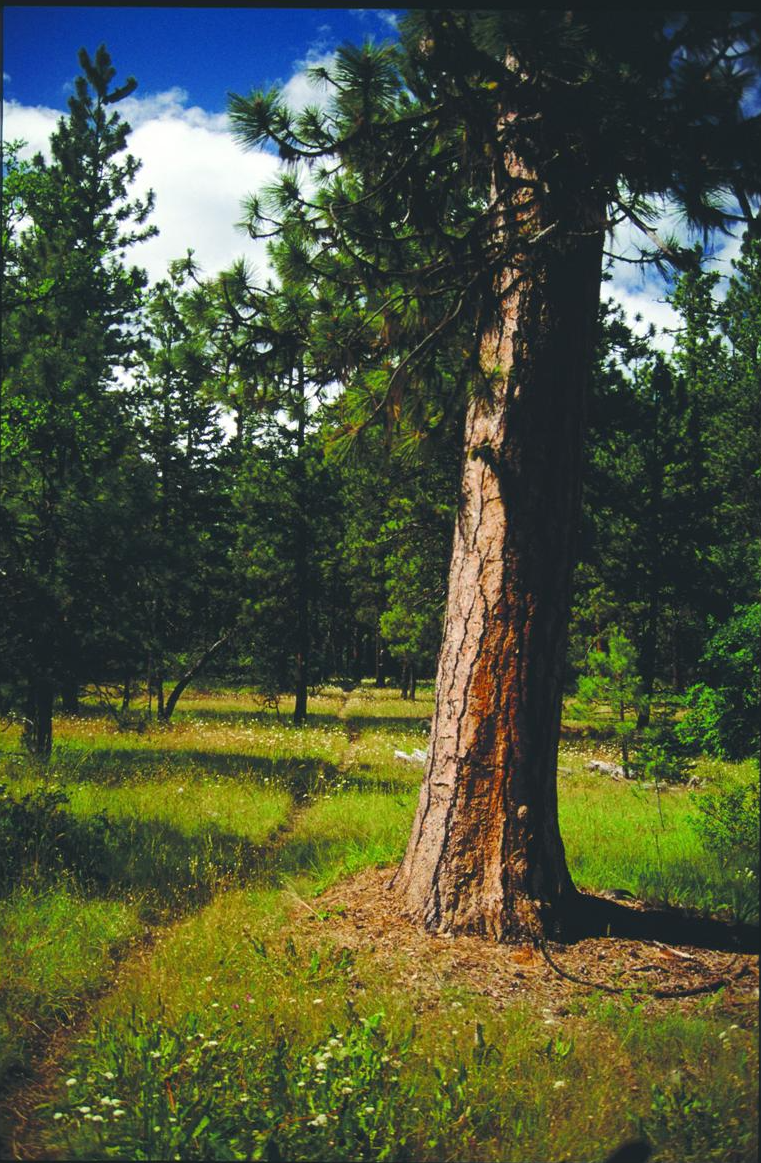

Figure 1. The Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail passes through Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument on Bureau of Land Management holdings in Jackson County, Oregon. This image first appeared in the book Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness. Source: Elizabeth Feryl / Environmental Images.

The National Trails System: Extent and Intent

The National Trails System Act (NTSA) begins like this:

In order to provide for the ever-increasing outdoor recreation needs of an expanding population and in order to promote the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation, trails should be established (i) primarily, near the urban areas of the Nation, and (ii) secondarily, within scenic areas and along historic travel routes of the Nation, which are often more remotely located.

In order of intended priority, the NTSA defined four kinds of trails:

1. National recreation trails (NRTs) “provide a variety of outdoor recreation uses in or reasonably accessible to urban areas.” Nationally, there are 1,295 NRTs in all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. NRTs, at least in Oregon, are further categorized into backcountry, equestrian, fitness, greenway, mountain bike, nature, rail, urban, water, and/or wilderness trails (here is a listing of Oregon NRTs).

A subset of NRTs are national water trails (NWTs), which the National Park Service has branded as the National Water Trails System. There are twenty NWTs so far, including the Willamette River Water Trail, managed by Willamette Riverkeeper. Though an NRT water trail, the Tillamook County Water Trail Systemis just a regular NRT, not an NWT.

2. National scenic trails (NSTs) “will be extended trails [more than 100 miles in length] so located as to provide for maximum outdoor recreation potential and for the conservation and enjoyment of the nationally significant scenic, historic, natural, or cultural qualities of the areas through which such trails may pass. National scenic trails may be located so as to represent desert, marsh, grassland, mountain, canyon, river, forest, and other areas, as well as landforms which exhibit significant characteristics of the physiographic regions of the nation.”

3. National historic trails (NHTs) “will be extended trails which follow as closely as possible and practicable the original trails or routes of travel of national historical significance.”

4. Connecting or side trails (CSTs) “will provide additional points of public access to national recreation, national scenic or national historic trails or . . . will provide connections between such trails.” There are only six established CSTs.

Notice that the National Trails System (NTS) was intended to be “primarily” about trails near urban areas, and “secondarily” about scenic and historic trails “often more remotely located.” Yet, it is the few longer scenic and historic trails that get more attention than the many shorter recreational trails.

An NST or NHT can only be established by an Act of Congress. Congress has occasionally legislatively established NRTs, but most NRTs are administratively designated. Each NST and NHT is administered by one of the four major federal land management agencies (see Table 1). Administration includes developing a trail management plan, overseeing trail development, coordinating trail marking and management, developing maintenance standards, coordinating interpretation, providing financial assistance, and more. However, the actual management may be done by another federal agency, a state or local government, private organizations, or individual landowners.

Map 1 is the latest and best map of the National Trails System. Map 2 is a clip of that larger map centered on Oregon. There is also an interactive map of national scenic and historic trails.

In 2009, Congress established an Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail, but it is not part of the National Trails System (Map 3).

Map 1. The latest and best map of the National Trails System (doesn’t include national recreational trails). Source: National Park Service

National Trails and Conservation

Alas, designation of a national trail brings more recognition than conservation—not only conservation of the user experience but also conservation of the many values the user experiences. This isn’t right. Read again what the NTSA says about NSTs: “National scenic trails [are] so located as to provide for maximum outdoor recreation potential and for the conservation and enjoyment of the nationally significant scenic, historic, natural, or cultural qualities of the areas through which such trails may pass” [emphasis added].

It must be said that the recognition afforded by the early establishment of the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails—the latter of which eventually linked the John Muir, Tahoe-Yosemite (both CA), Oregon Skyline, Cascade Crest (WA), and other through trails—was instrumental in achieving additional conservation of many areas of federal public land along the trail routes. Still, to know a natural area is to love it, and if that natural area is too well known, it can be loved to death. Excessive recreation use can harm not only the conservation of nationally significant natural qualities but also enjoyment of and on the trail, as too many hikers can kill the thing(s) they love.

A case in point involves the 1,200-mile-long Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail (PNWNST), which stretches from the Continental Divide to the Pacific Ocean very roughly paralleling the Canada-US border, established by Congress in 2009. Local grizzly bear lovers in the Yaak Valley, including noted author Rick Bass, insist that the trail be rerouted south of critical grizzly bear habitat. They argue that this is a more scenic route and would not impact the highly fragile local grizzly population of fifteen to twenty animals. The trail’s main advocate, the Pacific Northwest Trail Association (PNWTA), is opposed to the rerouting. The PNWTA website cautions about human–grizzly bear conflicts that could result in the death of the former but doesn’t mention potential harm to the latter. The New Yorker Radio Hour recently examined the conflict.

Grizzlies are protected under the Endangered Species Act. The Forest Service as trail administrator is preparing a comprehensive management plan for the PNWNST and should use its authority under and obligations to both the National Trails System Act and the Endangered Species Act to prefer grizzly bears over hikers. Of course, and especially, but not limited to, these days, a federal judge may be required to get the Forest Service to do the right thing by both grizzlies and the law.

Surprisingly, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has thrown his support behind the effort to reintroduce grizzly bears in Washington’s North Cascades ecosystem, also traversed by the PNWNST.

Long-distance trail use is not endangered in this country but is expanding. For grizzly bears, it is just the opposite. PNWNST users shouldn’t mind an even longer, more scenic walk as that is what generally motivates them. Even if they do mind, they must be made to avoid grizzly conflicts.

The short-term solution to the problem of too many trail users is to have more trails. The long-term solution is to have fewer trail users, by going back to a sustainable level of human population for the benefit of not only trails and the places they pass through but also for the various life-support systems on Earth.

Map 2. Parts of five national trails are found in Oregon: Pacific Crest (scenic), California (locally known as the Applegate Trail), Lewis and Clark, Nez Perce, and Oregon (all historic). Source: National Park Service.

Pending Congressional Legislation

Pending in the current 115th Congress are several bills that would extend or elevate national scenic and historic trails. Go to Congress.Gov and search for “national trails” and variants. Some of the more interesting bills seek to

• move the beginning of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail to the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from Wood River, Illinois;

• designate the Route 66 National Historic Trail; and

• establish a new category in the National Trails System of “national discovery trails,” including a first coast-to-coast national trail called the American Discovery Trail.

In the 114th Congress, Oregon senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley introduced legislation that would, among many other things, establish a half-mile-wide protective corridor along the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail administered by the Bureau of Land Management in Jackson County, Oregon. The purposes of the corridor would be “to protect and enhance the recreational, scenic, historic, and wildlife values of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail in as natural and undeveloped a state as practicable.” One hopes that this provision can be reintroduced in the next Congress.

Map 3. In 2009, Congress authorized the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail (not to be confused with the Ice Age National Scenic Trail in Wisconsin) to link geologic features created by a series of cataclysmic floods at the end of the last ice age (12,000–17,000 years ago) in Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. It is the nation’s only NGT and technically not part of the National Trails System. Source: Wikipedia.

For More Information

• The National Park Service has a National Trails System website.

• The Partnership for the National Trails System is a coalition of nonprofit organizations advocating for the National Trails System.

• “The National Trails System: A Brief Overview” is a nine-page report issued in 2015 by the Congressional Research Service.

• American Trails maintains a fine database of national recreation trails.