Steens Mountain Silver Jubilee, Part 2: Grand Bargain Details and Unfinished Work

This is the second in a series of two Public Lands Blog posts that examine the history of the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Act, which became law on October 30, 2000. Part 1 examined the creation of the grand bargain, while Part 2 details its specifics.

Figure 1. The Alvord Desert. Source: Dan Streifest, Flickr.

The Steens Mountain Act of 2000 was one of my (and others’) greatest legislative accomplishments. It elevated the conservation status of more than 1,000,000 acres of public lands. However, compromises were made; it also caused the privatization of nearly 86,000 acres (134 square miles) of previously federal public lands. Before agreeing to the Steens grand bargain, I consulted with greater sage-grouse, California bighorn sheep, and redband trout. They unanimously agreed it was a large net gain for nature. Although the land barons received millions of dollars of taxpayer monies, more than was financially fair, the exchange was politically pragmatic as it facilitated the establishment of a bevy of discrete and overlapping congressional conservation designations. Now, more remains to be done.

The Congressional Conservation Designations

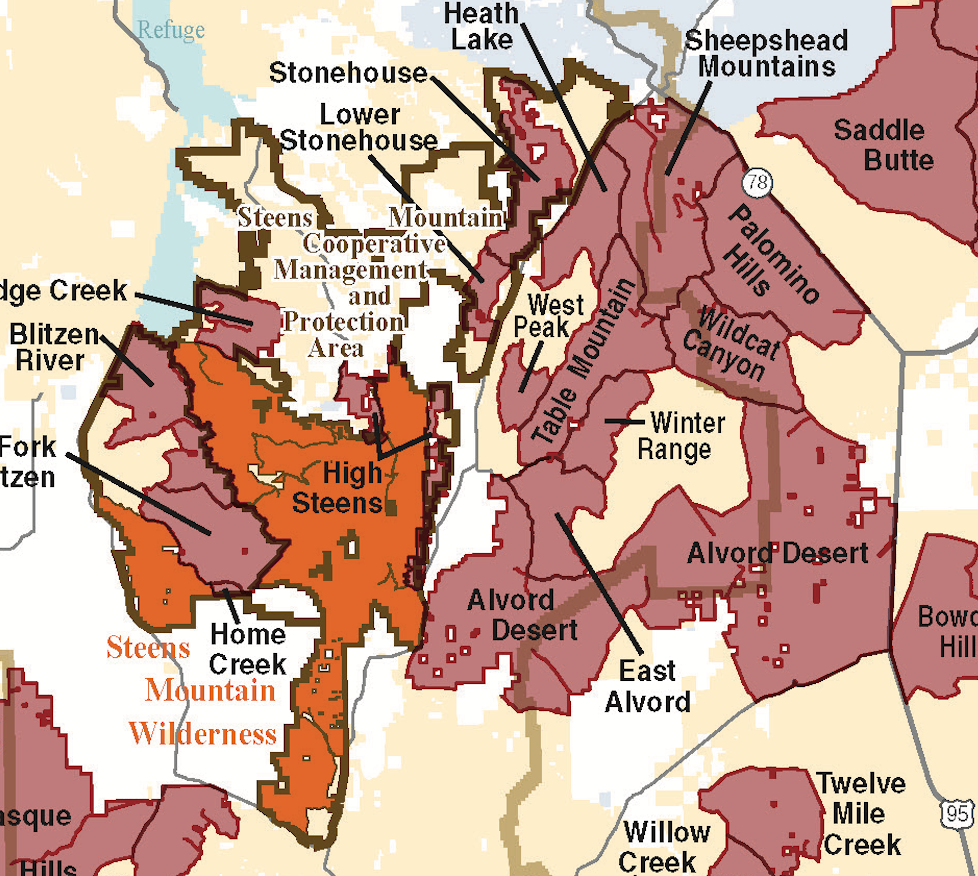

The Steens Mountain Act established several congressional conservation designations, as shown in Map 1 and Table 1 and described in the following sections. (Note that the acreages listed below are the numbers we were working with in 2000. Revised mapping has resulted in revised numbers, but the lines on the map have not changed.)

Map 1. My favorite map, showing all but one of the major conservation designations in the Steens Act of 2000. (Missing are additions to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System; see Map 2 for those.) Click on the image to expand to a more readable scale, and see the text commentary for the significance of the various colored lines. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Mineral Withdrawal Area

All public land within the turquoise outlines in Map 1 (1,148,158 acres) is withdrawn from all forms of mineral exploitation. At the time the Steens grand bargain was made, enviros were worried about geothermal development at the various hot springs near the Alvord Desert as well as cyanide heap leach mining for gold. Lithium exploitation was not on anyone’s mind back then, but if these lands had not been withdrawn, they would be in trouble today from the lithium boom, as well as from gold mining (with gold prices at $4,000/ounce). The disjunct outholding to the north is the Diamond Craters, which was vulnerable to mining although a designated outstanding natural area. The withdrawal area was the only protection afforded to the greater Alvord Desert.

Figure 2. Borax Lake chub. Removal of the threat of geothermal development around Borax Lake by the Steens Act was a contributing factor to the delisting due to recovery of the Borax Lake chub under the Endangered Species Act. Source: Fish and Wildlife Service.

Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area

The Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area (SMCM&PA), outlined in green in Map 1, is 496,135 acres in size. The Steens Act of 2000 states:

The purpose of the Cooperative Management and Protection Area is to conserve, protect, and manage the long-term ecological integrity of Steens Mountain for future and present generations.

Alas, additional “objectives” in the act tend to water down the “purpose” of the SMCM&PA. Still, better to have it than not.

Steens Mountain Wilderness Area

The Steens Mountain Wilderness, outlined in yellow in Map 1, includes five units: Alvord Peak (15,370 acres), High Steens (89,170 acres), Home Creek (20,740 acres), Little Blitzen (12,680 acres), and Upper Fish Creek (31,980 acres).(The acreages here and in Table 1 and Table 2 vary slightly—at most <3 percent—as sources vary.)

No Livestock Grazing Area

Most important, the statute required that domestic livestock grazing on 99,859 acres of the Steens Mountain Wilderness in the Donner und Blitzen River watershed (the No Livestock Grazing Area or NLGA, outlined in orange in Map 1) be permanently ended. Since the establishment of the first official wilderness area in the 1920s (with the help of Aldo Leopold), domestic livestock use has been grandfathered into every single wilderness area ever established where such use was occurring at the time of designation.

Wildlands Juniper Management Area

The Wildlands Juniper Management Area (WJMA, outlined in red in Map 1) was designed to help address the serious encroachment of the native western juniper into areas where it has not been historically. The major reasons for such invasion are the introduction of unnatural livestock and the exclusion of natural fire. This encroachment is having serious ecological effects on Steens Mountain and in many other areas throughout the arid West.

Section 501(b) of the Steens Act stipulates:

Special management practices shall be adopted for the wildlands juniper management area for the purposes of experimentation, education, interpretation, and demonstration of active and passive management intended to restore the historic fire regime and native vegetation communities on Steens Mountain.

Wild and Scenic Rivers

Congress established the Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River in 1988. The Steens Act added a total of 28.7 miles to the Wild and Scenic River System by adding Mud Creek (5.1 miles), Ankle Creek (8.1 miles), and South Fork Ankle Creek (1.6 miles) to the Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River, and establishing the Wildhorse and Kiger Creeks Wild and Scenic River, which includes Little Wildhorse Creek (2.6 miles), Wildhorse Creek (7.0 miles), and Kiger Creek (4.3 miles). Map 2 depicts these wild and scenic rivers.

Map 2. Wild and scenic rivers on Steens Mountain. The Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River includes several tributaries that drain northwesterly into Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. The two disjunct blue lines are the Wildhorse (south) and Kiger (north) Creeks Wild and Scenic River. Source: rivers.gov.

Map 2. Wild and scenic rivers on Steens Mountain. The Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River includes several tributaries that drain northwesterly into Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. The two disjunct blue lines are the Wildhorse (south) and Kiger (north) Creeks Wild and Scenic River. Source: rivers.gov.

Increase in the Wilderness Resource

Table 2 compares the acreage of officially designated wilderness and wilderness study areas before and after the Steens Act of 2000. The 13-percent net increase in the officially recognized wilderness resource is attributable to land exchanges that resulted in there being no publicly owned lands within the Steens Mountain Wilderness.

While resulting in a net gain in the officially recognized wilderness resource, the law did “release” some existing BLM wilderness study area acreage to either private ownership, the Wildlands Juniper Management Area, or general management within the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area (SMCM&PA) (Table 3).

After that net loss of 17,499 acres of wilderness study area lands, 118,344 acres of wilderness study area lands remain on Steens Mountain (Map 3). The parties could not agree on elevating these WSAs to wilderness status.

Map 3. The Steens Mountain Wilderness (in peach), wilderness study areas (in light pink), other BLM land (in tan), nonfederal land (in white), national wildlife refuge (in green), and State of Oregon land (in blue). Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Land Exchanges

Key to the Steens grand bargain were several complicated land exchanges and compensation to the land barons by the government. While the traded lands were of approximately equal financial value, the five land barons received ~$2,000,000 in additional compensation for new grazing infrastructure on the relatively undeveloped lands they received from the United States. One land baron was compensated $70,680 for losing grazing privileges in the NLGA.

If these land exchanges had gone through the normal administrative process, they would never have happened. There were no formal appraisals but only a “realty report.” The government land the ranchers received was priced at dryland grazing value, while the private lands the ranchers traded to the government were priced at recreation value. Only because Congress legislated the land exchanges did the Steens grand bargain come to fruition.

Financially, the land barons made out like bandits, but these land exchanges and related compensations were very much in the national public interest. Without them, there would be no Steens Mountain Wilderness, no additional wild and scenic river mileage, no NLGA, no Cooperative Management and Protection Area, no WJMA. The lands obtained by the BLM were of higher watershed, wildlife, and recreation value than the public lands transferred to private ownership.

Looking Forward

With congressional legislation, one generally needs to take what one can get when one can get it. One can live to lobby another day or another quarter-century. Congress should revisit the Steens Mountain–Alvord Desert landscape and further legislate for the benefit of these and future generations. Here are some opportunities.

Figure 3. The Heath Lake and Table Mountain wilderness study areas, part of the greater Alvord Desert landscape. Source: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr.

The Greater Alvord Desert

The Steens Mountain Act should be amended to include the greater Alvord Desert, which includes not only the incomparable Alvord Desert but also Mickey Hot Springs, Borax Lake and other hydrothermal features, Coyote Lake, and the Sheepshead Mountains. Most of the landscape between Steens Mountain and US 395 / OR 78 has been designated wilderness study area land and should be elevated to wilderness status (Map 4).

Map 4. The Steens Wilderness (in orange) and official BLM wilderness study areas (in brown). Significant portions of the other BLM lands (in tan) have wilderness characteristics. The SMCM&PA is outlined in brown. The greater Alvord Desert lies between Steens Mountain Wilderness on the west and US 395 / OR 78 on the east. Source: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr.

Besides including the existing Greater Alvord Desert Withdrawal Area in the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area, the boundary should be expanded to include other critically important natural features such as Tum Tum Lake, which has been established as a research natural area but is not protected from mining. According to the Pacific Northwest Interagency Natural Areas Network:

Tum Tum Lake Research Natural Area (RNA) was established to represent a low elevation playa lake bed and salt desert shrub community. Lodinebush (Allenrolfea occidentalis), salt heliotrope (Heliotropium curassavicum), and verrucose seapurslane (Sesuvium verrucosum) are the prevalent special status species found within the RNA.

Figure 4. The Tum Tum Lake Research Natural Area. Source: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr.

Livestock Grazing

Congress should extend the option of voluntary federal grazing permit retirement to the greater Steens-Alvord area, as would the Voluntary Grazing Permit Retirement Act (H.R.5785, 118th Congress).

Inholdings

The sponsors of the Steens Act promised, but did not deliver, money to acquire private land inholdings from willing sellers. The need still exists.

Administration

The administration by the BLM has not been as bad as I feared it might be, but it could be better. Objectively, the greater Steens Mountain–Alvord Desert landscape is national park–quality.

More Wilderness

The Steens Act of 2000 failed to designate some wilderness study areas on Steens Mountain as wilderness. Congress should now elevate these WSAs. In addition, other de facto wildlands known as lands with wilderness characteristics (LWCs) should be designated wilderness.

More Wild and Scenic Rivers

Free-flowing streams are important everywhere but especially so in arid landscapes. Several streams that arise both on the very steep east face and the gentler western slope of Steens Mountain are worthy of wild and scenic river status.

Figure 5. A Donner und Blitzen population of native redband trout. Source: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr.

Donner und Blitzen Dam Removal

It does not disqualify a stretch of river from consideration for wild and scenic river status to have a small dam or two. However, since a damn dam is harmful to the outstandingly remarkable values for which a stream segment is protected under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, it is appropriate to remove, or at least breach, such unnatural hunks of concrete and/or piles of dirt. The Steens Act of 2000 mandated rendering a small, but damming, impoundment of the Donner und Blitzen River within the Steens Mountain Wilderness unable to further harm the passage of native redband trout. Bureaucracies are slow, and in 2024 the BLM was finally getting around to it during the Biden administration, but it didn’t get done. The effort is on hold as long as Trump is in the White House.

See Public Lands Blog post “It’s About Dam Time” (2024).

Hammond Grazing Allotments

Some grazing allotments in the Steens Mountain Protection Area were previously held by a convicted felonious arsonist who was pardoned by President Trump in 2018. While the US Constitution allows a president to pardon a convict for crimes against society, he cannot pardon someone for crimes against nature. Along with their convictions, the grazing permittees lost their grazing privileges, which they now want back. The BLM is considering offering the allotment to the pardoned convicts or other ranchers. Instead, the BLM (better yet, Congress) should retire the allotments in furtherance of the Steens Mountain Act of 2000.

See Public Lands Blog post “Trump Pardons Abusers—Of Public Lands, Public Officials, and a Child” (2018).

Figure 6. Big Indian Gorge on Steens Mountain, in the Steens Mountain Wilderness, Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River, and Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area. Source: Bonnie Moreland, Flckr.

Bottom Line: The legislative protection of Steens Mountain was incomplete and needs to be completed.