TOP LINE: Oregon’s redrawn congressional districts will affect the prospects for federal public lands conservation.

Map 1. Oregon’s new congressional districts (click here for your own better-quality PDF). Source: Oregon Legislative Assembly.

The conservation of federal public lands in Oregon is very dependent upon the makeup of the Oregon congressional delegation. The 2020 census determined that Oregon would get another congressional district, for a total of six. The Oregon Legislative Assembly has determined the boundaries of the six congressional districts, and Governor Brown has signed the legislation into law (Map 1).

Litigation of the maps approved by the Oregon Legislative Assembly is highly probable but likely will be unsuccessful. The Republicans say the new districts are weighted toward Democrats. True enough, but not likely illegally so. The Supreme Court has found gerrymandering to be constitutional unless it violates the Voting Rights Act, which Congress enacted to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments (equal protection, right to vote, etc.) of the US Constitution.

Comparing the Old and New Maps

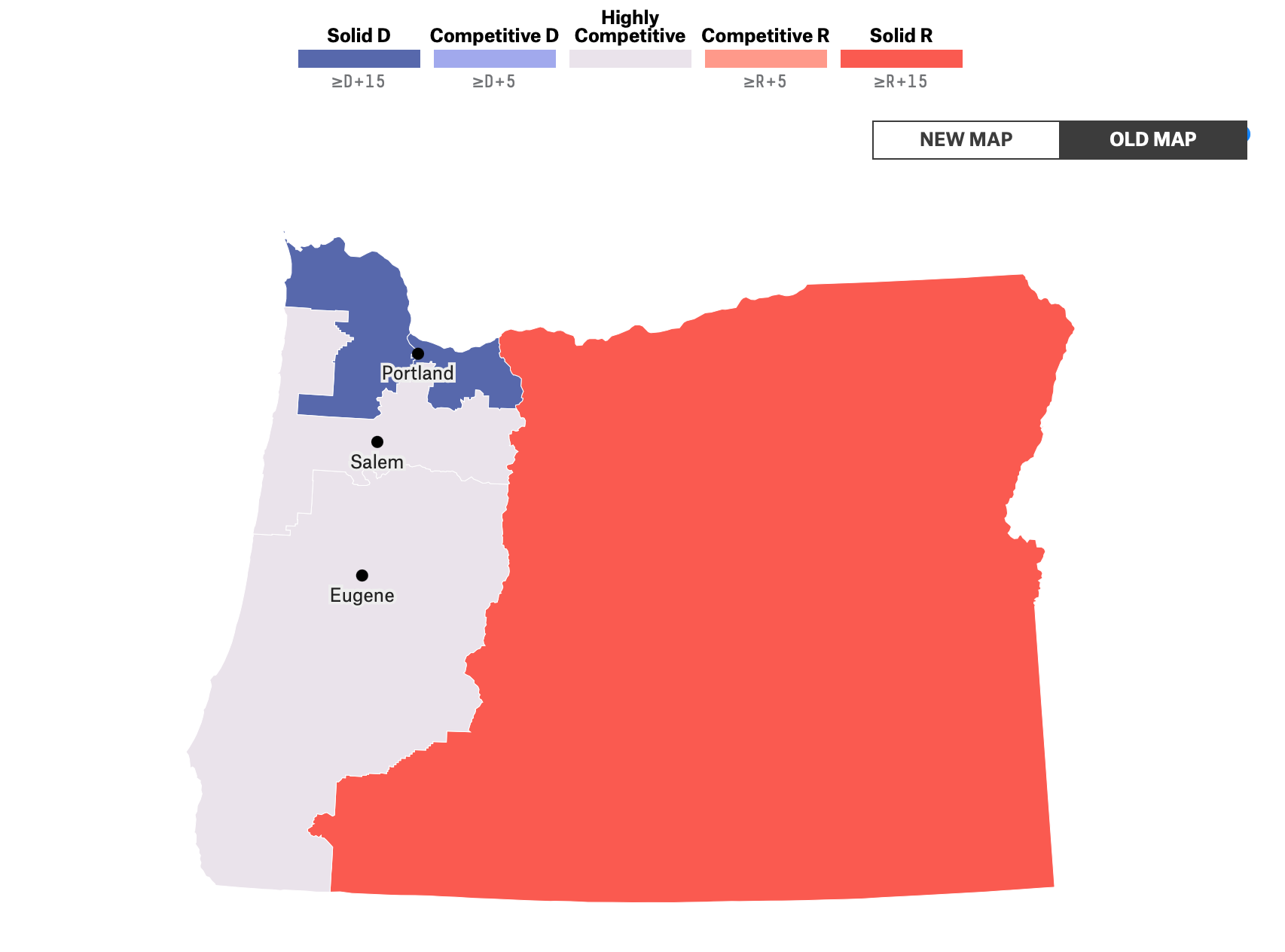

Oregon’s previous congressional districts had been in place since 2012 (shown with relative competitiveness in Map 2). The new map (shown with relative competitiveness in Map 3) is effective for the 2022 election through the 2030 election. For an interactive map, click here, then click on “Content,” then click on “Adopted Maps,” then click on “Congress (SB 881A).”

To see the evolution of Oregon’s congressional districts from 1971 (when there were only four districts) to the recent past, see my April 2018 Public Lands Blog post “A Sixth Congressional District for Oregon?” (If you really want to go deep into the weeds on congressional redistricting, I highly recommend davesredistricting.org.

Map 2. Oregon’s congressional districts 2012 to 2021, showing their relative competitiveness. Source: fivethiryeight.com.

Map 3. Oregon’s congressional districts 2022 to 2031, with relative competitiveness. Source: fivethiryeight.com.

Table 1. Oregon’s six congressional districts by land area and population. Source: Erik Fernandez, Oregon Wild; Oregon Legislative Assembly.

A Dozen Observations

In no particular order:

1. Douglas County, long entirely in Oregon’s 4th congressional district back to when Oregon got its 4th congressional district, is now split. Roseburg and North County stay in the 4th, but South County (even more conservative) goes into the 2nd district.

2. Losing south Douglas County, the non–Grants Pass portion of Josephine County, and almost all of Linn County (except the portion of Corvallis east of the Willamette River)—while gaining Lincoln County—will give incumbent DeFazio a party registration advantage (Table 2).

3. The new 2nd district is even larger in land area (74 percent of Oregon) than the old one (72 percent). Most of Oregon’s federal public lands are in the Oregon 2nd.

4. The Cascade Crest wall has been breached from the west. It has been the case for almost forever that the eighteen counties east of the Cascade Crest were in their own congressional district with enough people added from the west side to equalize population. The portion of Deschutes County with most of the people (sorry, LaPinians and Brotherites) is now in the new 5th district. I’ve long noted that demographically Bend is the easternmost extension of the Willamette Valley (sorry, Bendians), and the new map is evidence. Demographically closer to Portland than to Vale or Lakeview, Hood River County is now part of an expanded 3rd congressional district centered on eastern Multnomah County.

Table 2. Oregon’s six congressional districts by incumbent and partisan registration advantage. Source: Erik Fernandez, Oregon Wild; fivethirtyeight.com.

5. The new 6th district’s population is concentrated along Interstate 5 from Tigard to Salem. With no incumbent and a modest Democratic registration advantage, it is wide open.

6. The Democrats maintain a partisan advantage in all districts, save for the 2nd (Table 2). The slight reduction in the 3rd district and the significant increase in the 1st district won’t materially change the chances of Democrats winning those districts. As we go to post, State Representative Andrea Salinas (D-Lake Oswego) has announced her candidacy for the new Oregon 6th. Although Salinas chaired the House Redistricting Committee, she nonetheless lives a mile east of the new Oregon 6th in the revised Oregon 5th. To run for Congress in Oregon, one need only live in Oregon, not necessarily the district. Salinas has an Oregon League of Conservation Voters lifetime rating of 94 percent (100 percent in 2021 and 88 percent in 2019). Also announced for the Democratic primary is Multnomah County Commissioner Loretta Smith, who also doesn’t live in the new Oregon 6th. She’s retained a realtor but is awaiting the outcome of any court challenges to the new district lines before moving. Undoubtedly, more candidates will arise for this open seat.

7. Republicans have to be in some congressional district, so the Democrats packed more of them into their sacrificial 2nd district (Table 2), much, as a resident of Ashlandia, to my personal chagrin.

8. Representative Kurt Schrader is one of nineteen House members who have banded together as Blue Dog Democrats. A BDD was originally “a Democrat from a southern state who has a conservative voting record.” The geographic limitation is no longer operable. Although the geographic footprint of the revised 5th district has changed dramatically, Schrader’s formerly slight partisan registration advantage remains slight (Table 2). While his conservative posture has generally helped before general elections, Schrader should be concerned about being “primaried”—especially as Bend increasingly trends blue.

9. The new map was drawn fundamentally to protect incumbents of either party (Table 2). If I were drawing the maps, I would have spread the Democrats around more, making perhaps even the 2nd district competitive. Any advantage greater than D+20 is a total waste.

10. As the system is rigged to favor two major parties, all the focus is on Democrats and Republicans. It’s worth noting that there are more nonaffiliated voters in Oregon than Republicans, and if trends continue, nonaffiliated voters will soon outnumber Democrats (Table 3 and Graph 1).

Table 3. Oregon Registered Voters by Political Party, 2021. Source: Oregon Secretary of State.

Graph 1. All the parties listed in Table 3 are shown on this graph. Democrats (blue), nonaffiliated (gray), and Republicans (red) are along the top. Squeezed at the bottom are all the rest. (Squint and you’ll see different colors.) Source: Oregon Secretary of State.

11. Although most nonaffiliated voters loathe both major political parties, they consistently loathe one more than the other and will consistently vote for the same major party—though holding their nose. RINO is a pejorative label that stands for “Republican In Name Only.” There are also DINOs. However, most nonaffiliated voters in Oregon have proved themselves to be either RIFs or DIFs (Republicans In Fact or Democrats in Fact).

12. In the future, primaries will be the decisive elections. Oregon is dark blue, meaning Democrats, both registered and de facto (nonaffiliated in name but not action), will dominate elections—certainly statewide ones and in most congressional districts. At the state senate and house levels, Democrats have a strong numerical advantage by districts, but Republicans will still win in many. For those statewide or all-but-one congressional elections, the decisive election will increasingly be the primary. One can expect more Democratic incumbents to be challenged in their primaries. On the whole, this is a good thing.

How the Oregon Congressional Delegation Ranks on Conservation Among Its Peers

The lifetime scorecard rating of our delegation by the national League of Conservation Voters (LCV) is a rough approximation of an elected official’s placement along the dark green–dark brown political continuum.

Oregon’s two US senators, Democrats Ron Wyden (91 percent) and Jeff Merkley (99 percent) are generally quite green (Map 4), but each has his own significant brown spots that the LCV ratings don’t capture.

In the House of Representatives, Oregon currently has five members of Congress (from congressional districts 1 through 5): Suzanne Bonamici (98 percent), Cliff Bentz (first term; no rating yet), Earl Blumenauer (96 percent), Peter DeFazio (92 percent), and Kurt Schrader (86 percent). Again, there are brown spots in their records, except in the case of Bentz, where the green spot is the rarity (Map 5).

Map 4. Perhaps that new nation of “Ecotopia” offered in Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 novel makes some sense. Source: League of Conservation Voters.

Map 5. One Republican member and one middling Democrat notwithstanding, the Oregon delegation to the House of Representatives is dark green among the states. Source: League of Conservation Voters.

What Does the New Map Mean for Federal Public Lands Conservation in Oregon?

Former speaker of the US House of Representatives Tip O’Neill famously (but not originally) said, “All politics is local.” Today, far less so.

It used to be, at least back in the 1960s through the mid-1980s, that it was difficult—if not impossible—to get a wilderness area or wild and scenic river established if the local member of Congress was opposed. Wilderness areas and wild and scenic rivers were often established in Oregon’s 2nd district—always the largest in land area—from the 1970s through the mid-1990s. Though opposed, the member of Congress was nonetheless rolled by Oregon’s then senior US senator, Mark Hatfield. Being a powerful member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Hatfield made sure that the member he rolled could otherwise claim credit for having brought home important pork-barrel spending to the Oregon 2nd.

Here’s an example of how congressional district lines have mattered in the past. Construction on the infamous Elk Creek Dam didn’t start until 1982, when the damsite moved from the congressional district of a salmon-loving Democrat to that of a salmon-hating Republican. Actually, the damsite didn’t move, but the congressional district lines did. After a period of stasis when the dam sat half completed (but still killing salmon), the Army Corps of Engineers “notched” (breached) the budget-busting monstrosity. In 2019, at the insistence of Senator Ron Wyden, Congress included Elk Creek in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The Republican member of Congress at the time did not object, because—literally—most supporters of the damn dam had died.

Senator Wyden’s proposed River Democracy Act would establish or expand many wild and scenic rivers in Oregon, many of which are in the current and new 2nd congressional district, represented by Republican Cliff Bentz. A reason to pass RDA into law this Congress is that Bentz is in the minority, and the Democratic House leadership doesn’t particularly care about (or is it “particularly doesn’t care about”) what Bentz wants. If the Republicans regain control of the US House of Representatives, Bentz’s views on public lands conservation will be much more salient.

BOTTOM LINE: Of the two choices, Oregon and national public lands conservation are best served by Democrats holding the majority in the state’s delegation to Congress and in both houses of Congress.