This is the second of what were to be two but now are three Public Lands Blog posts that consider the desire of the Forest Service to amend a provision of the “Eastside Screens,” standards designed to protect public forests east of the Cascade Range. Part 1 examined the history, science, and politics leading up to the adoption of the Eastside Screens and their implementation since then. Part 2 explores issues both of management and of the science behind the management. Part 3 will suggest what the Forest Service could do to improve the Eastside Screens, in both the short and long term.

Figure 1. A low-intensity surface fire right now would knock back the young ponderosas and white firs that might otherwise compete with the old-growth ponderosa pines. Source: Larry N. Olson. (This image appeared in the book Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness, Timber Press, 2004.)

In the beginning, the Forest Service created the “21-inch rule” as one of many rules in the Eastside Screens. The “Interim Management Direction Establishing Riparian, Ecosystem and Wildlife Standards for Timber Sales”—aka the Eastside Screens—has been in place as “interim” direction since 1995. At its core, the rule says: Thou shalt not cut down a live tree larger than 21 inches in diameter measured at breast height (DBH, or 4.5 feet above the ground) on the eastside forests of Oregon and Washington.” The rule generally ended the massive liquidation of old-growth trees that had always been agency policy.

Now the Forest Service is proposing to “revise” the rule “in light of current forest conditions and the latest scientific understanding of forest management in areas that have frequent disturbances, like wildfires.” The leader of the agency effort takes great pains to say that the proposed change is narrow and surgical, and is based on the best available science. The agency has not yet publicly revealed the particular modification it will propose, but it will likely be an age-based cutoff rather than a diameter-based cutoff.

Just what age? The same age for all species? Will diameter (largeness) continue to count at all?

The 21-inch rule has both pluses and minuses. So would a rule based on age. But any rule should be based on science specific to the eastside forests and not extrapolated from science specific to the westside forests. And any rule should steer the agency to manage the eastside forests to serve their greatest need: more old trees, dead or alive.

Forest Service “Science”

The managers in the Forest Service’s National Forest System branch are relying on the scientists in the Forest Service’s research branch to produce the science to support the effort. Twelve scientists and other experts—all Forest Service employees—have produced a white paper entitled “The 1994 Eastside Screens—Large Tree Harvest Limit: Synthesis of Science Relevant to Forest Planning 25 years Later.” A problem with the white paper is that it makes numerous references to northern spotted owls. The very definition of the demarcation line between westside and eastside forests is that the former host northern spotted owls and the latter do not.

Furthermore, the white paper points out that livestock grazing, roads, and fire suppression are all problems in the eastside forests. Still, the Forest Service’s management branch has always refused—and continues to refuse—to address these issues.

As supporting resources for the plan amendment project, the Forest Service research branch offers up two chapters from its “Synthesis of Science to Inform Land Management Within the Northwest Forest Plan Area” general technical report, noting they are “relevant to” the Eastside Screens plan amendment project. While not irrelevant, the chapters are specific to the Northwest Forest Plan area—in other words, the westside forests. The absence of northern spotted owls is evidence that the eastside forests are significantly and materially different from the westside forests.

Perhaps because they were not given adequate time, the scientists have had to phone in the science. Where is the specific eastside forest research and synthesis?

The Administrative Elegance of the 21-Inch Rule

Inherently, bureaucrats want to maximize their discretion. They don’t like hard-and-fast rules that limit their actions. Managers argue that circumstances on the ground are varied and resist a one-size-fits-all approach.

Inherently, conservationists fear agency abuse of discretion and love unambiguously clear commands that limit agency discretion. Their experience has too often been that if Congress grants the agency discretion, the agency abuses that discretion.

Inherently, scientists know the world is neither black nor white, on nor off. So scientists tend to frame recommendations to agency managers in ranges rather than absolutes (for example, a riparian buffer should be between 150 and 300 feet, depending on . . . ). While scientists are correct in acknowledging varying conditions, they fail to recognize that bureaucrats are under pressure to achieve certain outcomes (for example, to get the cut out). Given those pressures, the 150 feet in the example becomes both the floor and the ceiling.

The administrative elegance of the 21-inch rule is that anyone with a D-tape (a diameter tape measure scaled in diameter though it actually is measuring circumference) will come up with the same result. No discretion is required, so no abuse of discretion is possible.

The Limits of the 21-Inch Rule

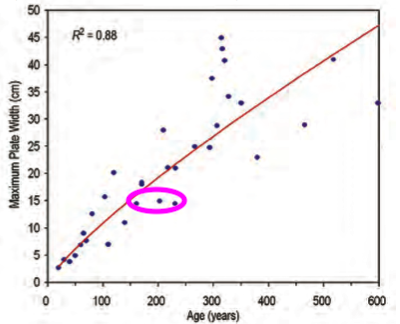

Not all old trees are large, and not all large trees are old. There is essentially a poor correlation between age and diameter (Figure 2). While trees all grow old at the same rate, trees grow large faster on more productive growing sites than on poor growing sites. In any forest, but perhaps especially in forests with fires of relatively high frequency but low intensity, both large and old are important.

Figure 2. The correlation between size and age for ponderosa pine in eastern Washington. Below the pink horizonal line are trees less than 21 inches (53.3 centimeters) in diameter at breast height. To the left of the vertical pink line are trees younger than 150 years old. Source: Robert Van Pelt.

The Eastside Forest Scientific Societies Panel recommended that the Forest Service no longer log large young, large old, and small old trees (see Part 1 of this three-part post). The 21-inch rule in the Eastside Screens means that the Forest Service does not allow logging of live large young and old trees, casting aside the small old trees. The agency now wants to log more large young trees and perhaps not log more small old trees.

Is Age a Better Management Metric Than Diameter?

Would an age-based cutoff for logging be a better management tool for eastside forests than a diameter-based cutoff? Yes and no.

First we have to consider whether an age-based cutoff can ever be as precise as a diameter-based cutoff. Remember: if discretion is required, abuse of discretion is always possible.

Before the early 1990s, to assess a tree’s age, one had to either core the tree with an increment borer or cut down the tree and count the rings before bucking it up and hauling it away, an option disfavored by wildlife everywhere. Regarding the first method, large trees need a big increment borer that requires massive strength to overcome the stresses put on it by a very large mass of wood, and the core often breaks even if the borer can reach the center of the tree.

Since the early 1990s, scientists have figured out ways to approximate the age of a tree just by assessing its looks. As trees age they tend to take on similar characteristics at similar times. One interesting metric is the size of the largest bark plate or patch of bark between the cracks in the bark. Robert Van Pelt of the University of Washington has done pioneering work on the metric. But this metric is not precise, and as Figure 3 shows, relying on bark plates to identify trees under a certain age for cutting can result in trees older than the cutoff age being logged.

Figure 3. While bark plate width is a better predictor of tree age than tree size, where the management line is drawn is critical. In the sample above, if the age cutoff were 150 years, the maximum bark plate width on trees marked for cutting would be 15 centimeters (2.54 cm = 1 inch, so ~6+ inches). In this sample graph, three trees over 150 years old and up to 225 years old with bark plates just under 15 centimeters in width would be logged using such a metric.

Another issue is that a diverse, healthy, and ecologically useful forest has trees in all cohorts. If the Forest Service cuts most of the small young trees because they are below a certain age, there might not be enough of the large young, large old, and small old in the future. Of course, the reason eastside forests are in such a state is that the Forest Service overcut the large—be they young or old—trees before the Eastside Screens were put in place. In most stands (outside of roadless areas, of which there is precious little acreage), the largest and oldest trees were the trees not worth taking the first (or second or even third) time, but are the trees that were next to be cut.

Then there is the fact that relying on any single metric for conservation is rarely a good idea. The Eastside Forest Scientific Societies Panel report suggested no longer logging both (1) any tree of any species 150 years old or older; and (2) any tree 20 inches DBH or larger. No, “20 inches” is not a typo. In fact, when the Forest Service chose their Eastside Screens, they specified 21 inches. In this case, the Forest Service took an inch and countless board feet went to the mill. Size matters. The Forest Service also decided that only live trees would fall under their 21-inch rule. The scientific societies panel report did not exclude dead trees in their recommendations.

The Need for More Old Trees

Eastside forests need more old trees, dead or alive. In general, due to fire exclusion, high-grade logging, and livestock grazing, the eastside forests (save for those at high elevations) have fewer large and old trees than they used to, but often more trees overall. This is because exclusion of relatively frequent but low-intensity fire (caused in part by the introduction of livestock) has interrupted the periodic natural thinning of stands. The result is that younger trees (sometimes ponderosa pine but often white or grand fir) are crowding out residual live old-growth ponderosa pine trees, turning them prematurely into snags—often not by fire but by insect or pathogen. In the normal course of events, these old-growth ponderosa pines would, on average, have another several centuries of life.

Don’t get me wrong. I love snags. Some of my best friends are snags. There is more life in a dead tree than a live tree. Eastside forests need more snags, especially large snags from old trees. However, eastside forests are also dramatically depauperate of very large old-growth ponderosa pine (aka yellowbellies).

The judicious killing of younger competing trees—whether by fire or chainsaw—can allow the older and larger trees to live. Please notice that judicious killing does not necessarily mean cutting down the trees, bucking them into logs, and hauling the logs to the mill. It can and often has, and that can be okay. However, a tree can also be killed in various ecologically friendly ways, including but not limited to

• reintroducing fire into the forest stand in ways that will kill most small trees and spare most large and old ones (Figure 4);

• letting forest fires burn to the same effect;

• gridling the tree so it dies from the outside in to become a useful snag;

• blowing the top off a tree so it dies from the inside out to become a useful snag;

• scorching the tree with a backpack flamethrower while on snowshoes to limit collateral damage;

• cutting the tree down and leaving it as terrestrial large woody habitat; and/or

• cutting the tree down and placing it in a nearby stream for large woody aquatic habitat.

Figure 4. The National Park Service, in this case in Crater Lake National Park, is reintroducing fire into fire-excluded stands without having to thin first. The Park Service is comfortable with fire, while the Forest Service still is not. Source: Elizabeth Feryl, Environmental Images. (This image appeared in the book Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness, Timber Press, 2004.)

Conservationists’ Concerns

While the Eastside Screens provide guideposts for land managers, the Forest Service scientists recommend that the Forest Service land managers have carte blanche. The rationale is that forests are complex and differ depending on latitude, elevation, aspect, species, precipitation, temperatures, and other factors, so one rule does not fit all. That is true, but one rule is superior to no rules.

Out of concern that the revision process is being driven by political and economic considerations, is dismissing the work of independent scientists, and is going forward at a time when public engagement is difficult, twenty-seven national, state, and local organizations (Figure 5) have jointly sent a letter to the Pacific Northwest Regional Forester that opens as follows:

For 25 years, these rules have provided a safety net for old-growth forests, large trees and structure, and wildlife in Eastern Oregon and Washington. They have also made it easier for conservationists, Tribes, local elected officials, logging interests, and the Forest Service to find common ground based on a clear understanding of what is and is not allowed on our public lands.

The letter goes on to allege that the process is being rushed, the effort relies on flawed science, and the public trust is being violated. It asks that the process be suspended and that any change in the rules be done through a process that is “balanced, transparent, comprehensive, and scientifically sound” and that “prioritizes wildlife protection, climate resilience, and public consensus.” Earlier, Oregon Wild, on behalf of some other organizations (including The Larch Company, my LLC), sent extensive “scoping” comments to establish standing and preserve their interests in the event of a legal challenge.

Figure 5. Organizations—including The Larch Company (moi!)—that signed a joint letter to the Forest Service critical of efforts to change the Eastside Screens. Source: Oregon Wild.

Part 3 of this Public Lands Blog series will offer recommendations on what course the Forest Service should take regarding the 21-inch rule and eastside forests in general.